The Digital Afterlife

Candice Chan

We live online in both life and death. Even after our physical selves come to an end, our digital footprint remains in the form of emails, likes, photos, tweets, Facebook profiles, Twitter, or Instagram accounts. All of this digital information that we accumulate over the years adds to our own digital profile and points to an interesting question: What happens to the information when we pass? Information is an essential part of our identity, but today, there is greater possibility of manipulating that original information than there has been before. This article aims to explore the commercialization of personal data and how the information we leave behind has contributed to the rise of afterlife services. The ideas presented explores when our digital lives begin, how our digital afterlife can be represented, who has power over our data after we pass, and the different afterlife services present today while shining light on the ethical questions related to power, identity, and privacy.

Where do our digital lives start?

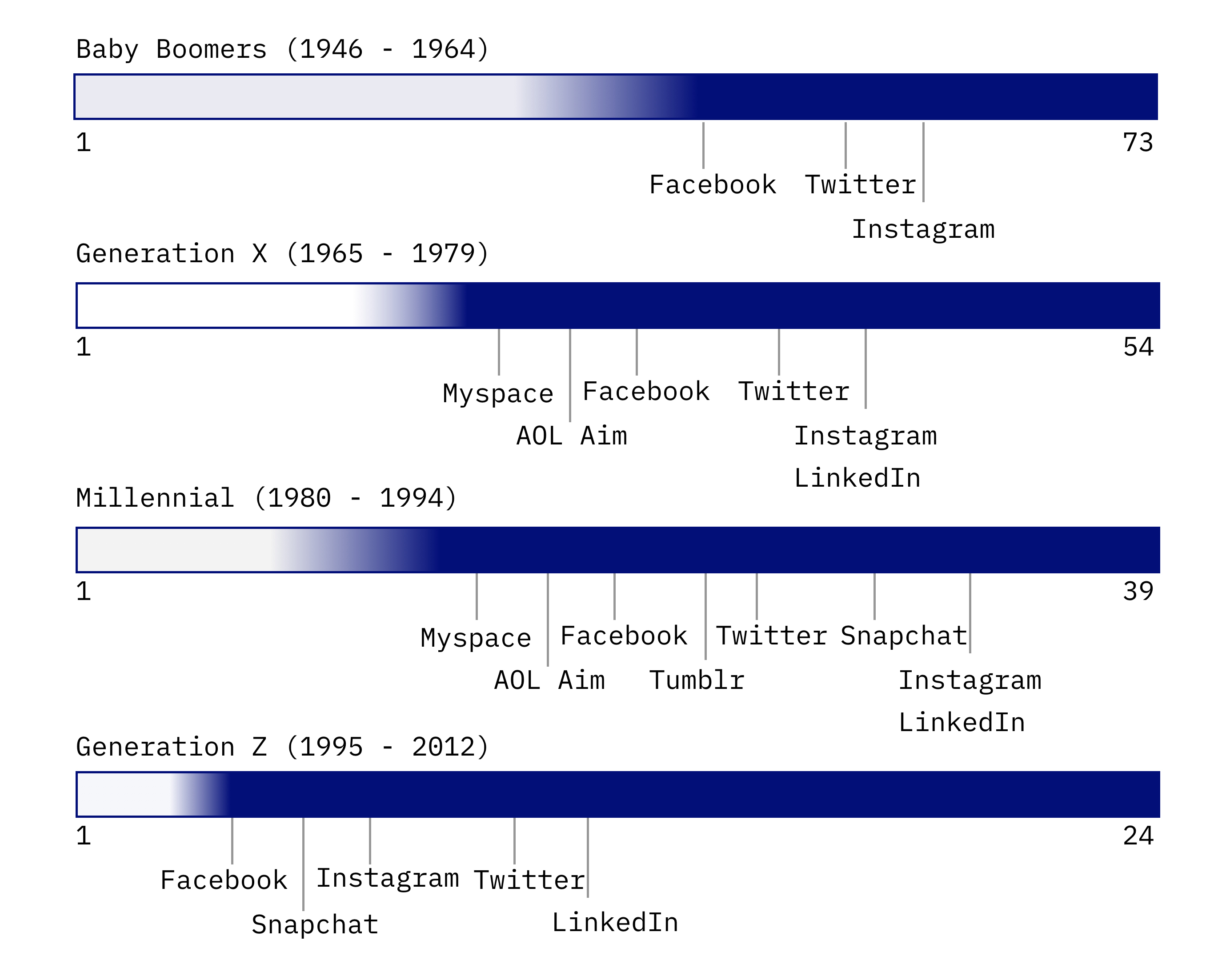

The internet may know us better than anyone else. Yet, when and where does this journey begin? When do we make our first mark in our digital lives? The following timelines represent the data collected by polling 20 of my own family members. Since the timelines only portray my family’s digital lives, cultural aspects remain constant, pointing only to generational characteristics as the cause for the timing difference in when people made their first online profile. For the purposes of the timeline, people were segmented into the four predominant generations that make up our population today:

By looking at the timelines, it is evident that Millennials and Generation Z have had greater and earlier digital interaction in their lives despite being half the age of Generation X, while Baby Boomers did not have their first encounter with social media until after their formative years. Since Millennials and Generation Z are cultivating their online and offline identities at a much younger age, one can only imagine the robust collection of data that could be accessible over a lifetime. Inevitably, conversations and debates surrounding transfer of trust and rights over data are most relevant to these generations as the privacy and security of personal information is at stake.

Who Has Power and Rights Over Our Data?

In American law, a trust can be arranged to specify exactly when and how assets transfer to beneficiaries. It is a three-party relationship in which the first party, the settlor, transfers a property to a second party, the trustee, for the benefit of the third party, the beneficiary. The main principle is that the “settlor’s intention is given effect to the maximum extent.” Nevertheless, trust law’s deference to settlors’ wishes has limits, reflected in the rule against capricious purposes, which prevents the owner who has passed away from doing something that the owner is free to do with his property while alive due to court ruling that the wishes stated are too eccentric. This point is played out in an interesting example in which a settlor firmly instructed to burn his Rembrandt art piece upon his death, but could not establish a trust to destroy it due to the revised rule that a trust and its terms must be for the benefit of its beneficiaries. In this case, transferring the art piece to a beneficiary with instructions to burn it is not to his or her benefit and, therefore, the initial plan to burn the art piece could not be carried out. This brings forward the question - how much should his wishes be respected? If he owns the painting, should he have final say on what is done with it? Does the cultural significance of a Rembrandt overshadow his wishes?

Within the digital realm, our online property and footprint is most likely the equivalent to the idea of burning a Rembrandt upon death. Although there would be far fewer negative consequences in eradicating our digital footprints in comparison to burning a valued artwork, deleting entire digital lives erases parts of the internet history that is vital in understanding a complete picture. If every tweet sent out during our lifetime were deleted, all the threads in which we participated would be broken and fail to tell the coherent message or topic in discussion. After we are gone, who ultimately has power over our data? Perhaps the only way to accurately portray how we want our digital selves to be preserved is to take the task into our own hands before we pass away.

Different Afterlife Services

In the past couple of years, the number of “dead” profiles on Facebook in the US has been estimated to increase at a rate of around 1.7 million per year. This statistic in addition to advances in technology has sparked the interest in the emerging industry offering people the opportunity to extend their digital agency beyond biological death. Some of these services are as simple as making sure key documents and passwords are available for executors and the bereaved, while others send out posthumous messages at a time of the deceased’s choosing. The multitude of services, while still gaining traction, are emerging at a time when people are more inclined to treat their digital property in the same way they do their physical assets. The main types of afterlife services in the market today are information management, posthumous messaging, online memorial, and recreation services. Each of these services focus on either the preservation of information, memories, and, to an extent, personalities.

Information Management Services

According to security company McAfee, the average Internet user puts an estimate of about $37,000 on their digital assets. Information management services help users with digital asset management and create a form of digital will to make sure that assets are passed on upon death. Google’s Inactive Account Manager is one example of an information management service which enables users to provide information about a contact who will have access to the account once the owner has been inactive for a set amount of time. After the set amount of time has passed, Google can automatically delete the account.

Posthumous Messaging:

Posthumous messaging services provide a more curated experience. Now that we are moving into augmented reality and the Internet of Things, there are new opportunities to modernize the memorial service industry. One example is Replika, a San Francisco based artificial intelligence company known for creating a chatbot which replicates behaviour and thoughts as people chat to it. It works by mimicking a person’s characteristics and building a persona that sounds and responds just as loved ones would.

Online Memorial Services:

Online memorial services are mainly focused on the bereaved by providing an online space for a loved one to be remembered. These sites allow people to come together, share memories, photos, videos, or other content to help build a space of reflection. Facebook allows users to designate a “Legacy Contact”, which allows the legacy contact to write a post to display at the top of the memorialized timeline, respond to new friend requests from family members and friends who are not yet connected on Facebook, and update the profile photos.

Re-creation Services:

Re-creation services use personal data to replicate a person’s behaviour. Perhaps the most rare of all the afterlife services, re-creation has yet to be adopted by technology giants. eterni.me, a young startup, plans to combine the online footprint - made up of everything a person has ever posted on social media, his or her thoughts, smartphone pictures and other aspects - with artificial intelligence to create a digital version of the person. Depending on the facts collected, the avatar will be able to offer anything from basic biographical data to being an engaging conversational partner. Although highly realistic, these re-creation services have the highest chance of exploiting grief and the greatest threat to afterlife privacy.

How Can Our Digital Afterlife be Represented?

With the rise of after life services comes the rise in ethical dilemmas regarding how our data is treated. Many studies have discussed the topic of creating systems that treat digital remains in a way that is not solely for commercial gains. In Carl Ohman’s study of the digital afterlife, he connects how human remains in archaeological exhibitions could be used as more ethical frameworks for digital remains. He argues that digital remains should be seen as information corpses, thus creating a more respectful mindset in handling personal data of those who have passed.

Although an interesting solution to the uncertainty of having our life’s worth of online data analyzed, perhaps another solution could be to reconsider the boundaries of life we are creating, starting at birth and continuing well after death. In a time when almost every pivotal aspect of life is digitized, from creating Facebook or Instagram accounts before babies form their first words to using AI chatbots to resemble our personalities, it seems as though special moments are experienced through digital mediums as opposed to in the moment. Death, as one of the only inevitabilities in life, should be left untouched by the digital realm. The growing efforts to “disrupt death” and build a person’s social immortality online will only disrupt a sacred event that should be treated with the utmost significance. Due to the pressures of the online world today, the youth of Generation Z are already forming well curated online identities at ages when they are still figuring out their likes and dislikes. Instead of bringing this mentality to the digital afterlife by developing ways to reincarnate a person online or curating profiles for the dead, the digital afterlife should be for the sole purpose of building tributes - reflecting upon lives well-lived and precious memories we yearn to remember most. □

References

- "Trust". BusinessDictionary. WebFinance, Inc. Retrieved 10 August 2017. (http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/trust.html)

- H. Langbein, John. (2010). Burn the Rembrandt? Trust Law's Limits on the Settlor's Power to Direct Investments. Boston University Law Review. 90. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228218243_Burn_the_Rembrandt_Trust_Law's_Limits_on_the_Settlor's_Power_to_Direct_Investments)

- Evans, C. 1.7 million U.S Facebook users will pass away in 2018. The Digital Beyond.

- Öhman, Carl and Floridi, Luciano, An Ethical Framework for the Digital Afterlife Industry (March 1, 2018). Nature Human Behavior, 2018, DOI.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0335-2 (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3172038)

- Öhman, Carl and Floridi, Luciano, An Ethical Framework for the Digital Afterlife Industry (March 1, 2018). Nature Human Behavior, 2018, DOI.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0335-2

Candice Chan is a MS Data Visualization student at Parsons School of Design