An Afternoon Walk Through Times Square

An Afternoon Walk Through Times Square

Peter Yu

There's a radiating intensity to Times Square. It's home to a great concentration of gawking bodies, mass-media advertising, expensive real estate, and cultural cachet. And because of all this, it's also a focus for the security state and digital surveillance.

One could look to the geographic legacy of the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, laying out Manhattan's street grid when only its Southern tip had been settled. It was a kind of spatial knowledge that , rather than describing the land, prescribed how it was to be sold and developed - a story told by city authorities and speculators over the claims of indigenous people and irregular property owners.

The grid was a triumph of reason over the landscape and human geography. Homogenous rectangular blocks denied any hierarchy or centricity. Straight ways were designed for optimal circulation. Conflicts were elided in construction through extensive works shaping and leveling the land.

The acute intersection of Seventh and Broadway as a chokepoint for traffic, people, and capital was one of many anomalies that went against the Plan's rational vision of architecture and culture. Broadway existed well before the Plan was laid out and only begrudgingly included, clashing with the Avenues at six awkward moments.

I knew that Times Square was under greater surveillance and scrutiny than other parts of the city. But I felt it only as a vague aura, an atmosphere that ramped up as I neared the 45th St intersection and fell down as I left. It made itself known to me plainly through the presence of police officers with badges speaking of counterterrorism; menacingly through the surveillance camera systems clearly marked "NYPD" but operating under shadowy domes and shadowy information systems; subliminally through the advertisements dictating how I should think and consume; behaviourally through the design of the pedestrian plazas and walkways; and intellectually through a kind of post-9/11 idea of what constitutes an attractive terrorism target.

The early 20th Century saw the accumulation of opulent theaters and hotels, the first billboards, and the image of Times Square as a center of pleasure and excess. But as the city's fortunes declined in the '60s, so did the nature of these pleasures, and in the tough-on-crime 90s, the city went about wiping the slate clean.

Based on a broken windows rationale that saw criminality as an urban miasma, police cracked down on crimes such as prostitution and drug possession - a shift from reacting to crimes to actively disciplining the behavior of ordinary people on the street. And geospatial methods took hold: the Midtown South precinct targeted their officers' ambient presence through intricate maps of crime and seedy establishments within those few blocks, pioneering the crime heat-mapping techniques that led to today's algorithmic policing methods.

Ultimately, the Disneyfication of Times Square came out of a patchwork of tax abatements and development deals designed to attract capital. Disney came to Broadway in 1994, Lehman put up today's advertising displays in 1995, and Times Square as a nauseating concentration of consumerist forces emerged fairly recently.

After September 11th, concentration became a liability. A lurid series of foiled plots on Times Square proved the need for increased police presence and a vast video surveillance system. Here, street crime is replaced with a stochastic threat, and for the normative "public," the smug shield of being a law- abiding citizen breaks down into the fragile status of having "nothing to hide."

The threat of vehicle ramming attacks came into the counter-terrorist imagination just as planners were experimenting with pedestrian design in the square. Thus bollards came into the architectural vernacular in forms ranging from concrete blocks to high-minded sculpture, delineating spaces of particular value.

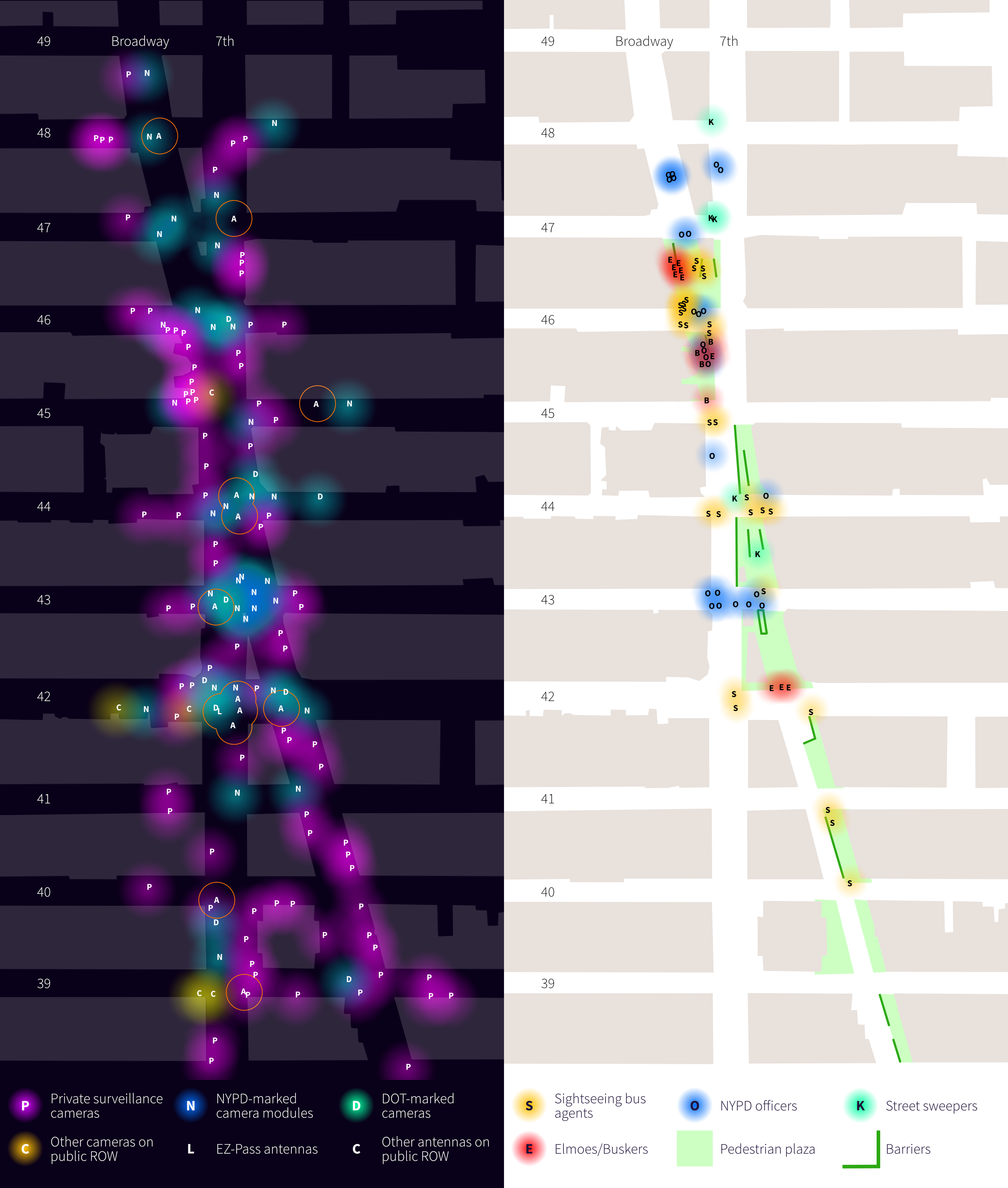

As I see it, surveillance technologies in public space manifest in specific devices yet have a presence over a range of effects - a camera's field of view and the antenna's direction and power. Spread enough of these devices around, and this presence can totally envelop a space. Having little clarity on the systems they connect to, I set out to better understand surveillance in Times Square by way of what is visible.

I took two trips to Times Square, walking North along Broadway and then South along Seventh Avenue between 39th and 48th Street (roughly the span of the pedestrian plazas). I kept my eye out for items of interest as I proceeded, and plotted their distribution on the map.

On the first trip, I looked up at the air - cameras, antennas, and other devices mounted up high - focusing on video surveillance equipment. I encountered a veritable menagerie of communications devices on light poles, bulbous, boxy, spindly, shiny, flat. Many were mysteriously unmarked; some had identifiable agency or manufacturer logos, and some were loudly proclaiming "NYPD / Security Camera." I categorized them by institution - the NYPD's video surveillance program, the DOT's traffic monitoring system, private businesses (whose footage often makes its way to the police), and unknown cameras on city infrastructure. I found myself perceiving my path differently, linking my physical presence to a floating grid of devices, feeling their presence become denser as I neared the heart of Times Square.

On the second trip, I looked at the uniformed staff who maintain the circulation of people and money, acting as the eyes on the street, their distinctive uniforms linking their presence in space to their institutions' imperatives. Police presence was predictably dense, a cluster of four or five doing very little on every central cross street, a show of force more than anything else. Tour bus vendors scanned the sidewalk for customers to harangue while costumed characters loitered around, daring tourists to take a picture.

I come out of this exercise with an appreciation of the spatial dimension of surveillance, and in particular, of the sheer frequency and concentration of video surveillance points. Passing through Times Square on this mission, I felt exposed and circumspect - especially since I was exploring security infrastructure. I felt my person accumulating on recordings like dirt accumulating on my skin, a hygiene- anxiety response to my identity spilling across networks with no way to take it back. I felt my body moving on a track, knowing there was a safe and acceptable way to navigate the plazas, the people, and the traffic.

Ultimately, this wasn't anything I or anybody else didn't already know. Civil liberties groups have done in-depth mapping investigations on electronic surveillance and counterterrorism policing in New York. And it's not a surprise that the panopticon broadcasts its presence. Perhaps this little exercise has shown is that, although the security state may appear (and be) untouchable, it necessarily occupies a physical presence which can be addressed.

References

“E-Zpass Readers.” New York Civil Liberties Union, 25 June 2018, https://www.nyclu.org/en/e-zpass-readers.

“New York Is in Danger of Becoming a Total Surveillance City.” Amnesty International, 16 Aug. 2021, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/06/scale-new-york-police-facial-recognition-revealed/.

Sheidlower, Noah, et al. “Vintage Photos: The Evolution of Times Square from 1898 to Today.” Untapped New York, 1 Oct. 2014, https://untappedcities.com/2014/10/01/vintage-photos-the-evolution-of-times-square-from-1905-to-today/.

Sheidlower, Noah, et al. “Fun Maps: The Times Square Vice Map of 1973.” Untapped New York, 9 Sept. 2014, https://untappedcities.com/2014/09/09/fun-maps-the-times-square-vice-map-of-1973/.

“Security Tour of Times Square.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 7 May 2010, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2010/05/09/nyregion/20100509-critic-audio.html.

“NYC Streets.” Commissioners’ Plan, https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2010/05/09/nyregion/20100509-critic-audio.html.

Glueck, Katie, and Ashley Southall. “As Adams Toughens on Crime, Some Fear a Return to ’90s Era Policing.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 26 Mar. 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/26/nyregion/broken-windows-eric-adams.html.

McMenamin, Michael, and Michael McMenamin. “From Dazzling to Dirty and Back Again: A Brief History of Times Square.” Museum of the City of New York, 30 Aug. 2016, https://www.mcny.org/story/dazzling-dirty-and-back-again-brief-history-times-square.

Stern, William J., et al. “The Unexpected Lessons of Times Square’s Comeback.” City Journal, 18 June 2019, https://www.city-journal.org/html/unexpected-lessons-times-square%e2%80%99s-comeback-12235.html.

Gottlieb, Martin. “New Times Square.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 28 Jan. 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/01/28/nyregion/new-times-square.html.

Editors, The. “Times Square, Bombs and Big Crowds.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 3 May 2010, https://roomfordebate.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/05/03/times-square-bombs-and-big-crowds.

Surveillance Cameras in Times Square, http://www.notbored.org/times-square.html.