Bodies, Maps, and Cities

The Implications of the Quantified Self in “Smart” Cities

Karen El Asmar

Introduction

It might be hard to imagine but there was a time not so long ago when very few mobile phones were in use. A time when people still communicated via landlines and people did not know how many steps they had walked at the end of each day. These days are long gone. Digital technology has developed so much since then, and so too has our reliance on it. All around us, technologies ranging from wearable sensors to hands-free devices have become seamlessly integrated into our lives, changing the way we experience the world. It has revolutionized how we work, how we exercise, and even how we rest. However, although wearable devices - such as smart watches, smart glasses and fitness bands - have largely captured the public’s attention, they’re just a small part of a much larger story. Urban developers have the potential to integrate personal analytics in urban infrastructure by promoting the use of wearables, analyzing collected data, and making policy decisions based on that data.

Today, new wearable technologies are being developed that connect people to objects, other people, environments and infrastructure. These new ways of connecting have given rise to the phenomena of "smart cities." These wearables monitor heart rate, temperature, people’s voices, the position of their shoulders, hands and feet, even the chemicals in their blood and bodies. Linking people to private and public infrastructures and the services that run through them is believed to be important for helping authorities anticipate people's needs and respond to them more efficiently. However, this also enables companies and authorities to get their hands on our most intimate data. Despite the fact that personal data collection on this scale may be useful for city planning, what are the implications of having such data in the wrong hands or being applied in unintended ways? What information can be extracted from these data and how can it be used?

Although not connected to wearables yet, companies such as Related, the company behind Hudson Yards, already has the infrastructure to track people’s movements, interactions, behaviors, and even identities. This tracking is done by cameras, sensors and Wi-Fi kiosks distributed in the area. The kiosks aim to relay to advertisers how many people look at an ad, for how long and most importantly, their facial expressions. Advertisers claim facial expressions relay information about whether people are interested, happy, or bored. Related is moving closer to the wearable industry by creating an app for its residents, Related Connect, that aims to replace keys with smartphones. A feature of this app, Pass, created for office buildings, scans biometric fingerprints of tenants to allow them into the building 3.

The implications of such sensors moving closer to and analyzing our bodies - faces and fingerprints - is much deeper than simply having access to certain services or evaluating ads. When combined with other data that could and will be collected, can give information about people’s health, and eventually their emotions. Such data could be of great interest to companies who are desperately looking for ways to better understand the desires of city residents. Companies especially interested in this kind of data include real estate companies hoping to understand distribution of emotions, and advertising agencies who aim to benefit from quantifying these emotions for branding purposes. Cities such as New York, are not prepared for these technologies. This is especially concerning because as of yet there are no data-sharing agreements between the city and the real estate companies. Nor are there any city laws regarding data collection that would apply to real estate companies. Due to this lack of regulation companies are automatically allowed to indefinitely keep this data and use it for whatever purposes they desire.

In response to the these concerns, I decided to undergo an experiment to investigate the social, cultural, economic, and political implications of having a wearable technology that collects people’s intimate biometric data. The possession of data of this nature could potentially lead to interpreting, our innermost states and desires. I was also interested in what mapping my own biodata would reveal. This experiment is a critical reaction and an exploration of the current desire for technology to quantify our biodata and the dominance of bio-tracking technologies.

Methodology

I first identified the variables I wanted to measure based on what information might be of interest to city authorities and companies. These areas of interest included facial expressions for purposes of ads, heart rate for measuring excitement and fear, and a distance sensor measure traffic. I designed and built a portable device that would record data that relates closely to the human experience in a city. Through this approach, I hope to explore the relationship between the internal state of the body within a wider urban context. Studies show that there is a correlation between facial expressions, heart rate, and emotions 1 2. These studies have lead to the assumption that this type of data collection could potentially lead to an interpretation of my emotions. Mapping data as points on a map would allow for the recording of the geographical location of where these emotional changes occur in a city.

The Experiment

The Tool (Sensors)

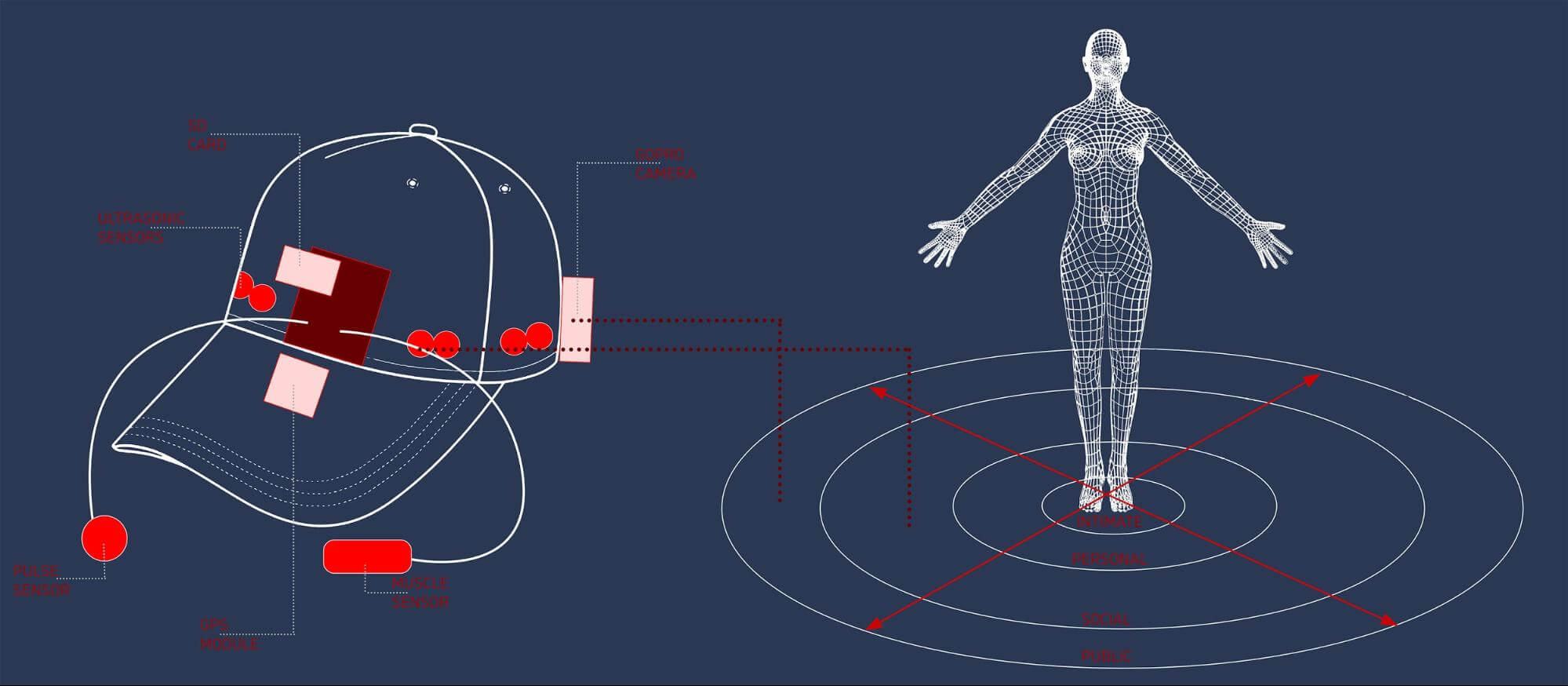

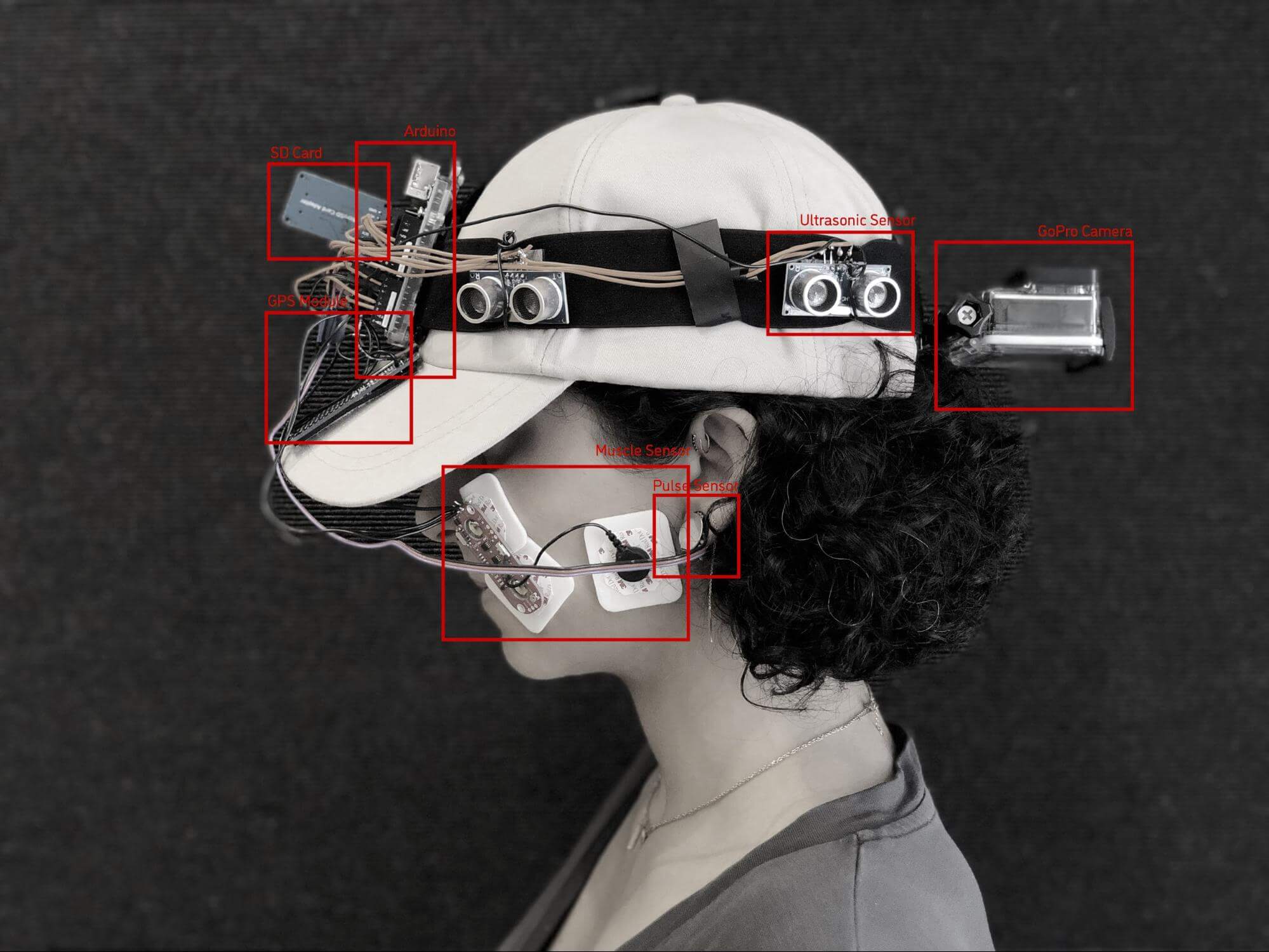

I identified the sensors based on Edward T. Hall’s proxemics theory. The proxemics theory classifies four main spaces around the human body: the intimate space, the personal space, the social space and the public space. In each of those spaces I use a sensor that can measure a characteristic of this space. I collect data from 5 main sensors: a pulse sensor, a muscle sensor, a distance sensor, a GPS sensor and a camera.

The Form

As for the form of the device, I hacked an everyday object to perform my experiment: a hat. By augmenting the hat with sensors, I will hopefully be able to map, articulate, and eventually interpret this data about my own multi-sensory experience in the city.

The Path

As for the path, walking through the different areas of Manhattan would have been the most accurate approach. Due to the scale of this project, I decided to create a path that I believe would cross through some of the city’s “multiple personalities.” I walked from 34th street - a central transportation hub - through Hudson Yards - “the smart city experiment” - through Chelsea - a bourgeois neighborhood - finishing on 16th Street, Greenwich Village. Along this path, I passed through commercial streets, glass skyscrapers, residential neighborhoods and ended up on another commercial street on 5th Ave and 16th Street. This path is inspired by the work of Charles Montgomery who created, with scientist Colin Ellard, a city experiment to explore the effect city spaces had on people. They found that people were happier and more friendly in front of “jumbled up messy old blocks” rather than in front of “a pristine new mixed-use block.” 5.

Performing the Experiment

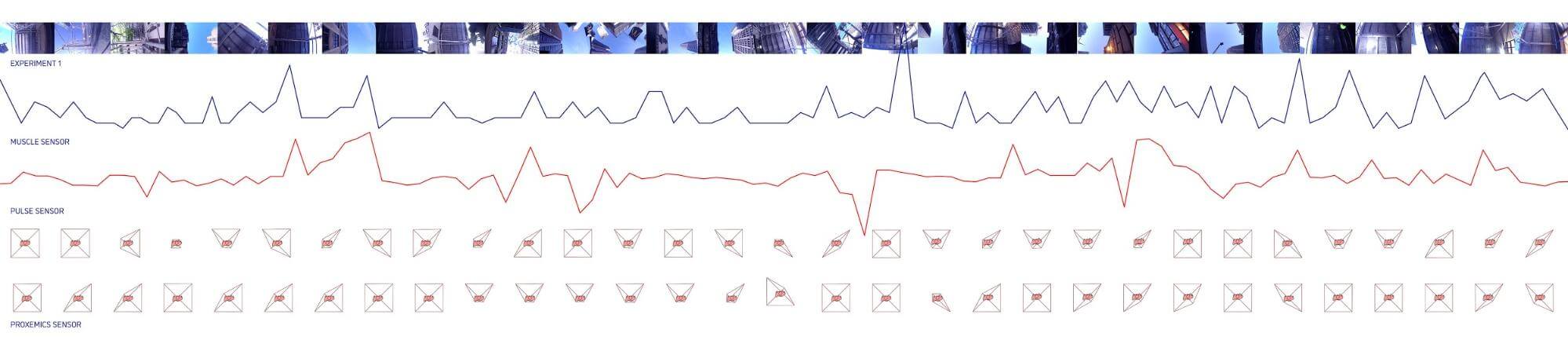

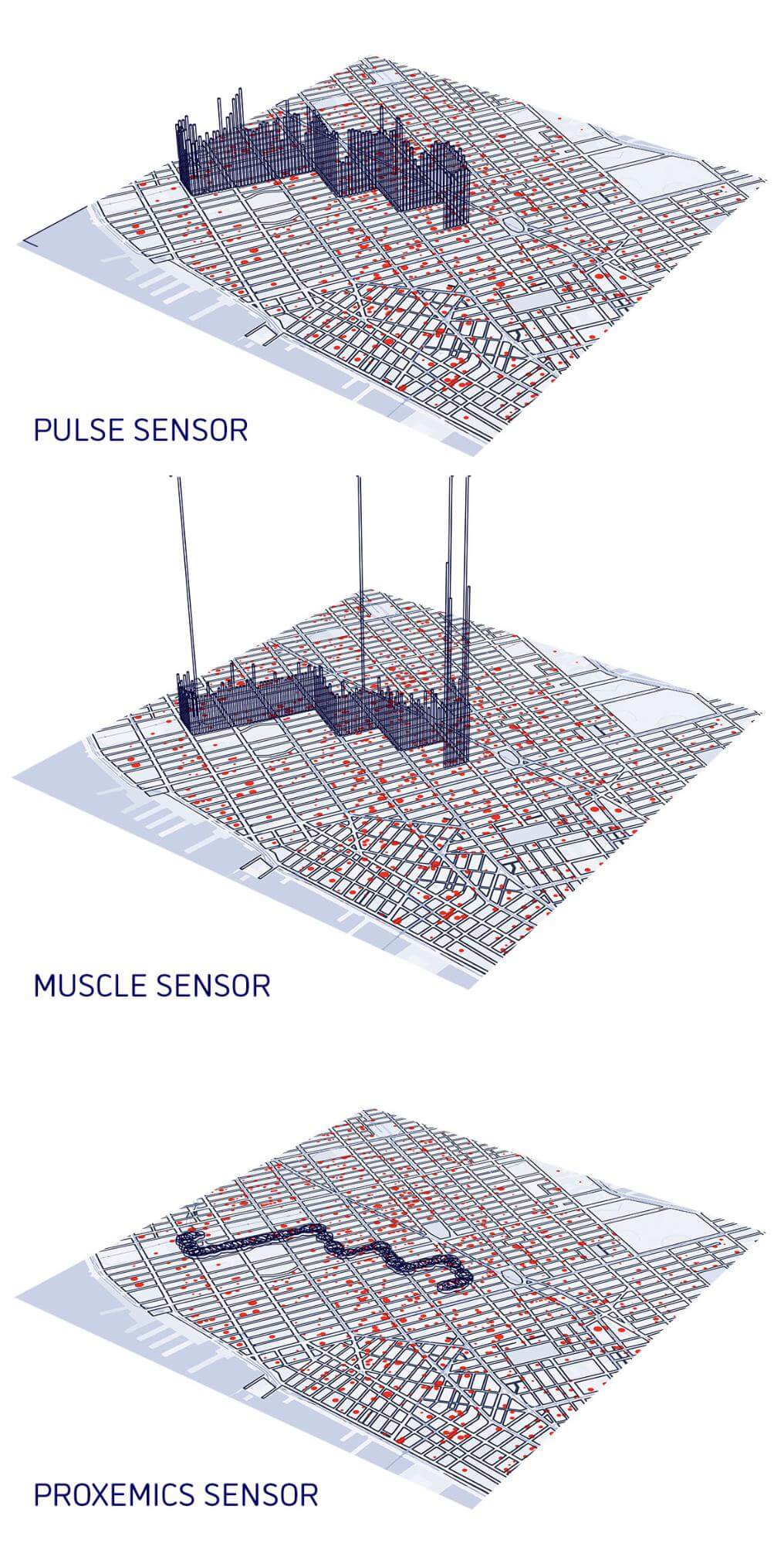

The Results

After collecting the data, I visualized it using Grasshopper. The result reveals my journey as a visual track on a map: height indicates my heart rate and my muscle tension at a particular moment, the circles reveal the proximity of people around me at certain moment in time.

My Reflection

After doing this experiment and observing the data, I realized that the personal benefits of such a device could be huge. The device I created is definitely not a perfect piece of technology that accurately measures my biodata. But, it has provided me with an adequate tool to gain a new type of knowledge of myself. By combining my biometric data, my geographic data and the subjective story in my head with a map, I gained insight into both my body and mind in relation to the city. This device allowed me to to make the internal world become external and, use it as a vehicle of self-awareness. Looking at this map, I am able to pinpoint locations where I felt my data changes and possibly recount certain events and memories that could have triggered these changes.

While collecting this data, I couldn’t help but wonder about a very central question: Is this walk I am taking just like any other walk on a spring afternoon? What is the significance of me mapping this walk? Who will use the data I am producing? And if not me, who will interpret this huge amount of emotion data / personal biodata? Will it be interpreted by software, by people, or some other conscious minds?

To me, the trails drawn of my experience are full of meaning and stories. However, taking a step back from it, I realize others would see this representation as a fairly random trail of points and lines. While I saw an intimate documentation of my journey, I also saw that when this information is collected and stored, there is an inherent risk of it falling into the wrong hands.

Looming over the idea of being able to see what people think and feel is the spectre of social and mind control. Throughout history, biometric technologies created were used as tools of state control and as tools that rewrite the notion of self. In fact, the mapping of the body is seen as the first step in its governance and in the subjugation of its boundaries to regulation and control 4. For this reason, real estate agents, car companies, wearable technology firms, and advertising agencies have rushed to get into people’s heads to see their most intimate feelings and desires. These companies, and government authorities want to gain insights into the geographical distribution of desires, a driver’s stress levels, people’s health risks. They would like to emotionally rebrand entire cities.

Another concern is that once in use, people may not be allowed to, or want to live without these gadgets. It is difficult to imagine why or when and under what circumstances one would yield complete personal privacy to the scrutinizing apparatus of power. I believe this performance of power requires the means to visualize people as transparent vessels of data to be collected. By this, the true test of citizenship then becomes about the degree to which one is prepared to make him or herself known to the state. This offering of personal information to those in power provides us with a “legal” place in the state and forces us to manifest what the state desires us to be.

Conclusion

Experiencing how self tracking technology was easy to build, useful to use, and personally insightful I think it’s only a matter of time before people start accepting this technology on an even larger scale. With the right technology, mapping our biodata could provide us with the ability to accurately visualize sensations we are not currently aware of. The ability to combine the experiences of people in a city presents us with a bottom-up process of identifying communal matters of concern thereby allowing for a new approach to city planning and problem solving. However, we must reflect on what the future of such mapping could mean: will it become a method of control? A revolution against authorities? A community consultation service? Or even a brain “enhancement” tool? The importance of confidentiality in regards to our personal data cannot be stressed enough. It is only when technology experts, governments, and organizations collaborate to develop comprehensive security and privacy standards that these technologies should be linked to our city infrastructure. Until then, questioning every device is the best practice. □

References

- Chang, Chuan-Yu, et al. “Emotion Recognition with Consideration of Facial Expression and Physiological Signals.” Emotion Recognition with Consideration of Facial Expression and Physiological Signals - IEEE Conference Publication

- “Identifying Correlation between Facial Expression and Heart Rate and Skin Conductance with IMotions Biometric Platform.” IMotions, 18 Feb. 2019, imotions.com/publications/identifying-correlation-between-facial-expression-and-heart-rate-and-skin-conductance-with-imotions-biometric-platform/.

- Jeans, David. “Related's Hudson Yards: Smart City or Surveillance City?” The Real Deal New York, The Real Deal New York, therealdeal.com/2019/03/15/hudson-yards-smart-city-or-surveillance-city/.

- Media Collective, Raqs. “Machines Made to Measure: on the Technology of Identity and the Manufacture of Difference.” Emotional Cartography , pp. 10–25, www.emotionalcartography.net/.

- Talks, TEDx. “The Happy City Experiment | Charles Montgomery | TEDxVancouver.” YouTube, YouTube, 24 Dec. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=7WiQUzOnA5w.

Karen El Asmar is a creative technologist, an experience designer and an architect who is currently based in New York City. Her work today falls at the intersection of architecture, art, science and technology.