Your Trash is You

Sean Scanlan

Overview

This project critically examines the quantified self through reusing and analyzing digital trash. It uses discarded screenshots as the raw data to create new images and analyzes these images using machine learning. Ultimately, it’s an exploration of the aesthetic and information potential of digital waste within the context of the shifting, increasingly machinic nature of visual culture.

Images as records: three stages in the process towards a trash-based quantified self application.

Introduction

The quantified self movement is about using technology to track aspects of a person's life with the underlying assumption that more data leads to greater personal insight and “positive” changes in behavior. Gary Wolf, a co-founder of this movement, described it as “self-knowledge through self-tracking with technology.” Most often this is applied to biometric data: people wear devices that tell them how many steps they take or how much they’re sleeping. This project instead considers something which is simultaneously more banal yet potentially more personal: the screenshots we take and then discard. In Living in the End Times

The intent of this project was two-fold. On the one hand, to highlight the absurdity of this sort of neoliberal drive towards automation by using digital trash to create more digital trash, and on the other, to see if this newly minted trash could offer any sort of insight into ourselves. The end result is a command line application that saves deleted screenshots and uses byte manipulation to create recombinant images from these personal fractured records of ourselves. Then, the program takes these recombinant images and runs them through a machine learning algorithm, trained on the Mobilenet dataset, to generate captions for the images before depositing them in the same folder screenshots are initially stored in. The application both creates new trash for you (thus automating the non-useful task of producing screenshots yourself) and offers a potential glimpse into what a machine thinks you’re looking at, based on the broken, distorted imagery created by reconstituting miscellaneous screenshots into one image.

Process

The process to arrive at this application took a few turns along the way. I started by writing a program to store deleted screenshots. It watched the trashcan on my computer and every time a file named “Screen Shot” followed by some date was dropped in the trash, it copied the image to a separate, hidden folder on my computer.

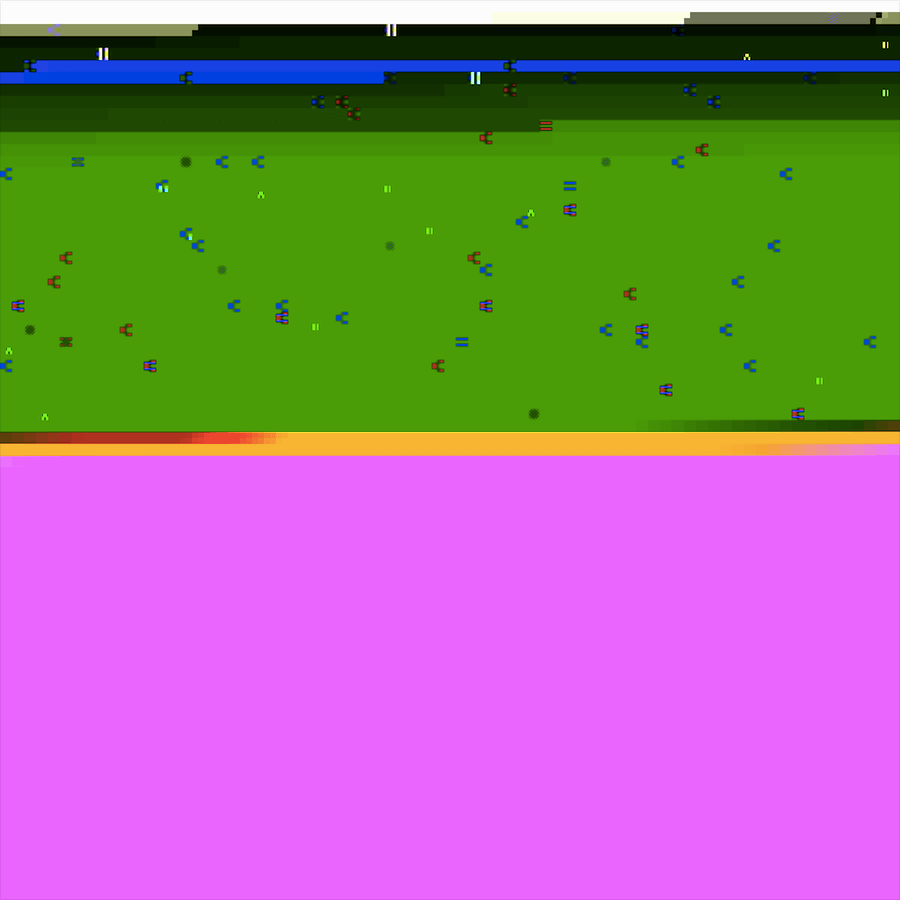

Three screenshots that were thrown away.

I played around with different ways to combine and reconstitute these images. First, I used the ImageMagick command-line tools to make composites of the screenshots, taking a few at a time and blending or multiplying them to create new images. However, these felt overly-constructed and seemed both too close to the original images and somewhat overly aestheticized.

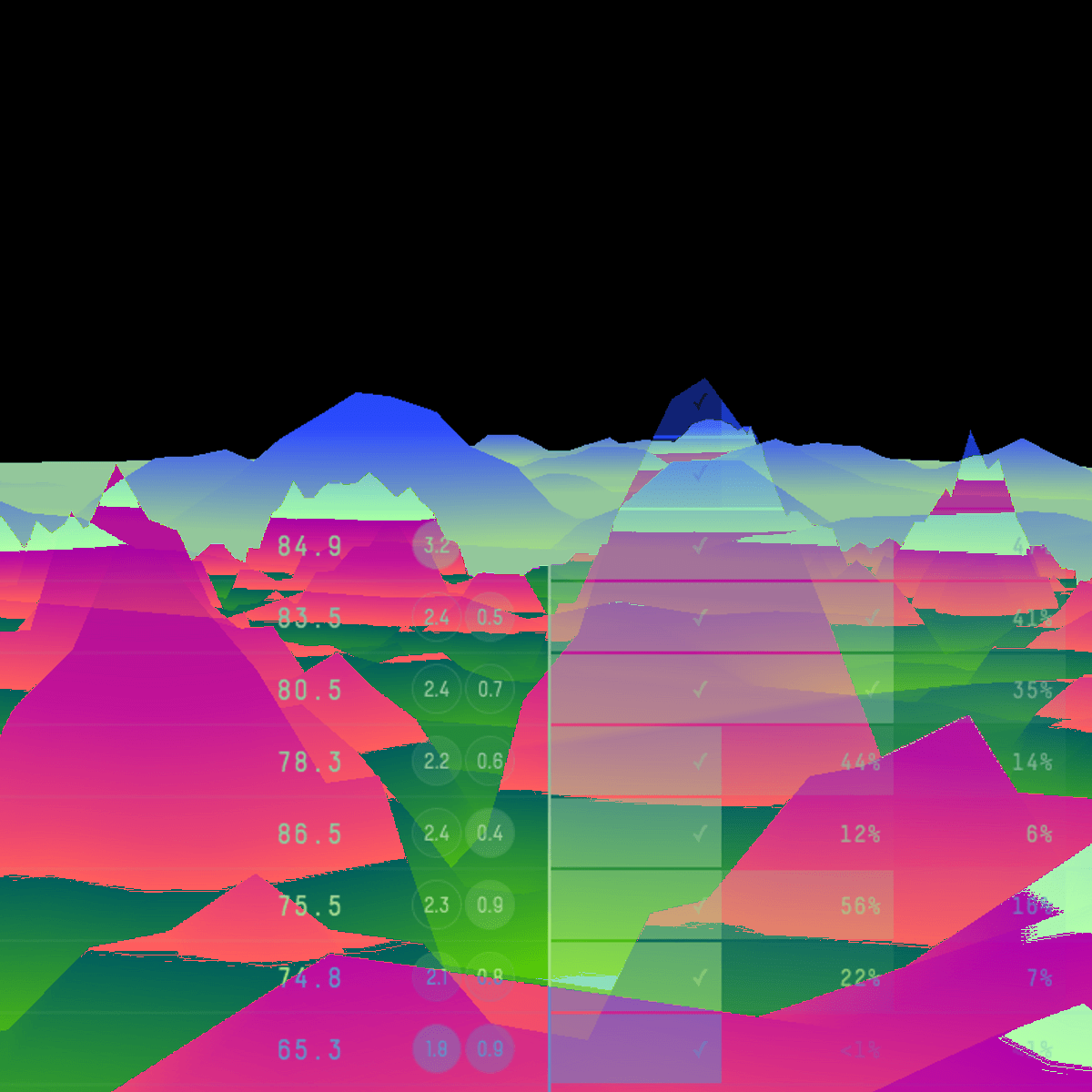

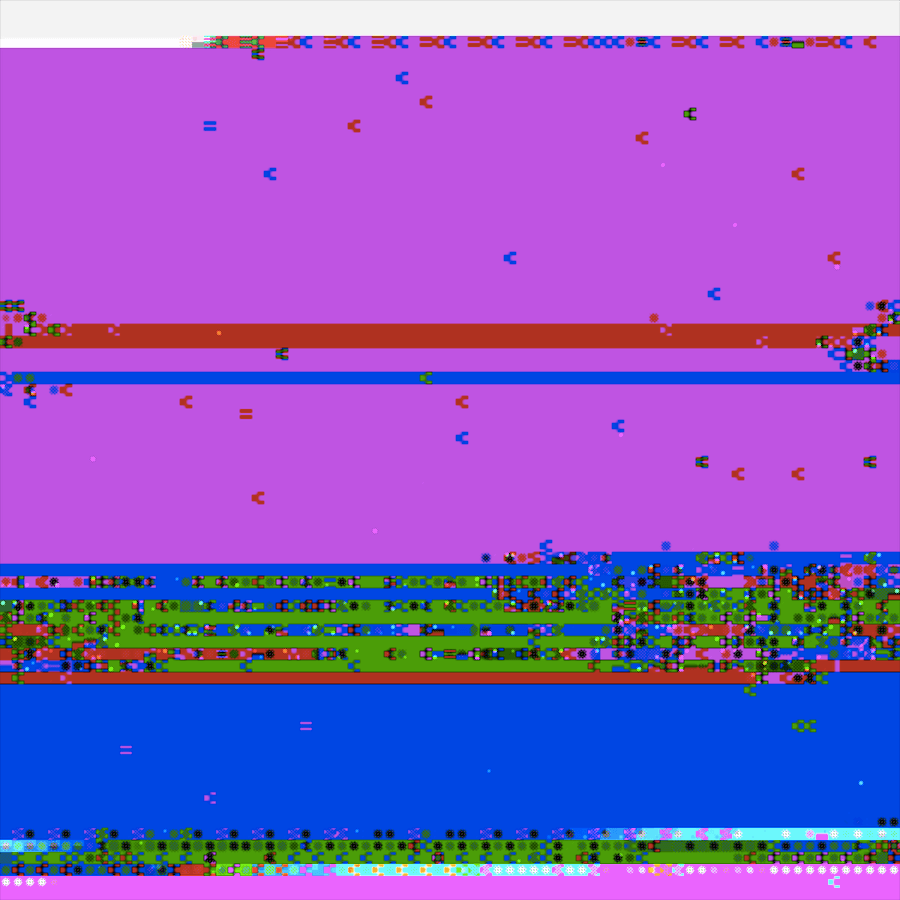

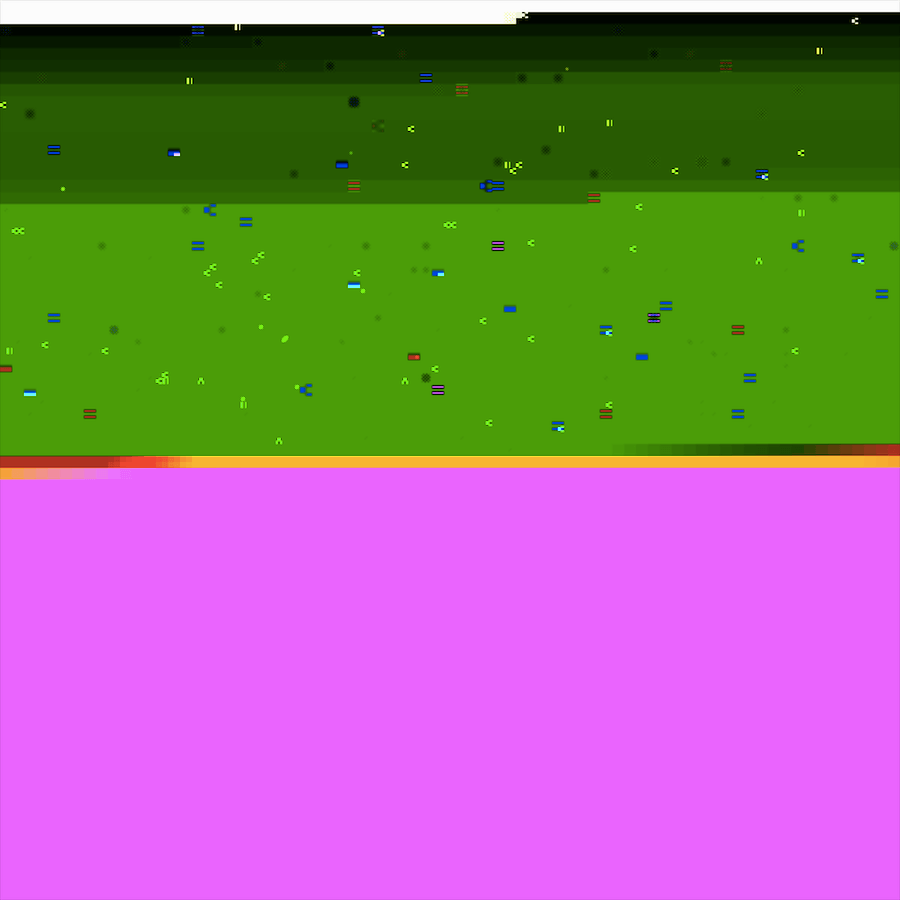

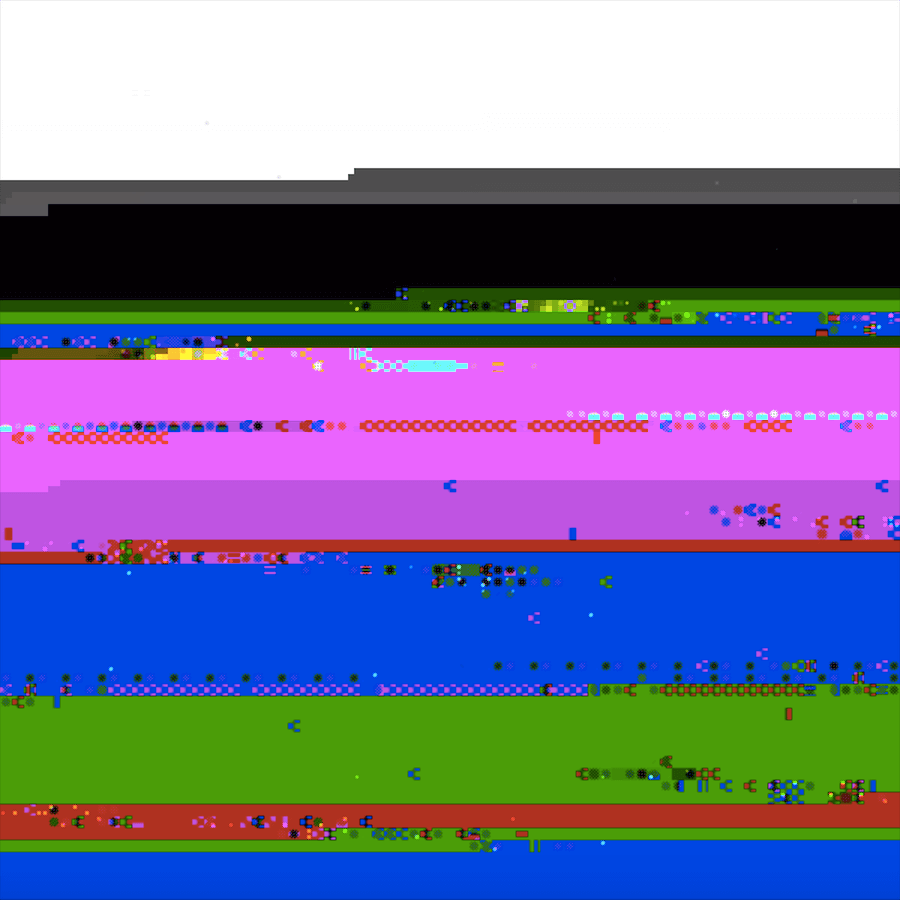

Three composites made from discarded screenshots

I decided to follow the thread of these deleted images as records, and create recombinant images from the record. In other words, I treated this corpus of records as a collected whole and constructed images from it. In order to create an image that incorporated data from all the screenshots I took bytes from all the images while keeping the .jpg header information. This also had the benefit of mimicking the act of digital deletion. When a file is deleted the pointer to that file is removed, allowing new information to be written in the registers containing the old data. To construct these new images I took the bytes from one randomly selected image and went through overwriting the data using bytes from all the other images. This resulted in glitches images which, interestingly, were so broken that my computer would display them differently every time I opened them (yet not so broken that the computer would refuse to open them entirely).

Similar to how glitched images appear visually disjointed, the computer was unable to provide stable visual representations of them. The next logical step felt like using machine learning to decipher these glitched images, or at least consider what they might mean to a machine. I then created another application that generates a glitched, recombinant image with the bytes of all these screenshots, classifies this image using the Mobilenet model, and moves this image to the desktop with the classification as the name of the file. Suddenly, “file_file-cabinet_filing-cabinet_printer_television_television-system.jpg” appears on the screen. Interestingly, while the computer was unable to display a consistent visual output for these glitched images, the machine learning algorithm would consistently return the same description of the image.

printer_file_file-cabinet_filing-cabinet_upright_upright-piano.jpg

Analysis

The end product is an application that produces digital garbage based on the user’s deleted screenshots: images with machinic descriptions, informing us what the computer sees in these recombinant images. In the essay “The Terror of Total Dasein”

printer_web-site_website_internet-site_site_analog-clock.jpg

While on the one hand this project jokes about neoliberalism, it also produces these images that, while visually broken, are constituted from meaningful and personal material. Since we cannot interpret these images in a meaningful way, and the quantified self movement is all about extracting meaning from personal data, it follows that for this project we should allow machines to interpret them for us. In “Ghost World,”

When studying works of art, or visual media, we know the litany of questions to ask to decipher an image. Who made the image, and how, and why? What does it show, intentionally and unintentionally? What is its purpose? What does it do? These questions, popularized by John Berger and others, have spread well beyond the academy and the art world to form the baseline of media literacy. But as images proliferate exponentially and their conditions grow more opaque, deciphering them becomes more difficult — not least because humans are no longer privileged interpreters.

Steyerl is interested in exploring how people will adapt to this changing environment of unintelligible (operational, encrypted, broken, and so on) images. However, on one level this project is concerned with the disconnect between what computers see and what we see in relation to recombinant digital records.

Matchstick_web-site_website_internet-site_site_radio_wireless.jpg

In “A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition”

As Trevor Paglen points out in “Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You),”

rifle_revolver_six-shooter_six-gun_trombone.jpg

References

- Slavoj Žižek. Living in the End Times. (Verso, 2018), 35.

- Hito Steyerl. “The Terror of Total Dasein.” Dis Magazine, http://dismagazine.com/discussion/78352/the-terror-of-total-dasein-hito-steyerl/.

- Rachel Ossip. “Ghost World.” N+1 Magazine, Fall 2018, https://nplusonemag.com/issue-32/reviews/ghost-world/.

- Hito Steyerl. “A Sea of Data: Apophenia and Pattern (Mis-)Recognition.” E-Flux, April 2016, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/72/60480/a-sea-of-data-apophenia-and-pattern-mis-recognition/.

- Trevor Paglen. “Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You).” The New Inquiry, 8 Dec. 2016, https://thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/.

Sean Scanlan is a living human in the North East United States. He has a website.