Beginning with Walter Mignolo and Madina Tlostanova’s assertion that “[t]he modern foundation of knowledge is territorial and imperial,” 1 Walter D. Mignolo and Madina V. Tlostanova, “Theorizing from the Borders: Shifting to Geo- and Body-Politics of Knowledge,” European Journal of Social Theory 9, no. 2 (2006): 205. this essay examines a select moment in the historical development of the internet through the lens of coloniality. It continues by speculating on the possible means through which we arrive at a decolonial internet, where the internet may instead be used to disrupt logics of extraction and subjugation. The notion of colonialism might initially seem distant from present-day discussions about the internet, particularly when understood as “a practice of domination involving the subjugation of one people by another through military, economic and political means.” 2 Walter D. Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh, On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), 116. This is especially so in today’s context, with the independence of postcolonial states being well-established. 3 Mirca Madianou, “Technocolonialism: Digital Innovation and Data Practices in the Humanitarian Response to Refugee Crises,” Social Media + Society (July–September 2019): 2. However, this essay operates with the understanding that colonial inequalities continue to persist and evolve for the contemporary moment. 4 Madianou, 2.

Following Aníbal Quijano’s notion of the coloniality of power, it may be understood that the subjugation of colonized communities takes place beyond direct colonial rule. 5 See Aníbal Quijano, “Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America,” International Sociology 15 (2000): 215–232. It endures today through the dominance of Euro-American perspectives in knowledge systems, systemic racial and ethnic discrimination, and the pervasive reach of global capitalism, for instance. 6 Madianou, “Technocolonialism,” 2. This finds connections in the seminal work of Ann Stoler on contemporary global inequalities, which are the “refashioned and sometimes opaque reworkings […] of colonial histories.” 7 Ann L. Stoler, Duress: Imperial Durabilities in our Times (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 5, as quoted in Madianou, 2. Colonialism’s extraction of resources underpins global capitalism, and “extractivism” extends beyond just material resources, including processes such as data mining. 8 See Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, “On the Multiple Frontiers of Extraction: Excavating Contemporary Capitalism,” Cultural Studies 31, no. 2–3 (2017): 185–204. It is through this nexus between data, extraction, and online platforms that the internet is entangled with the coloniality of power.

In speculating on a decolonial internet, the case study emerges from the postcolonial context of Singapore, an island-city state that is a highly connected node within broader transnational fiber optic cable networks for the internet, while simultaneously complicit in extractive uses of material resources and labor in Asia. 9 See, for instance, Joshua Comaroff, "Built on Sand: Singapore and the New State of Risk," Harvard Design Magazine, Fall/Winter 2014, https://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/articles/built-on-sand-singapore-and-the-new-state-of-risk/ and Ben Westcott and Katie Hunt, “Most Singapore Foreign Domestic Workers Exploited, Survey Says,” CNN, December 4, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/28/asia/singapore-domestic-helpers-maids/index.html. The internet often carries assumptions of being a global information infrastructure that confers political agency in its ability to ‘democratize’ flows of information, affording greater political participation through its decentering of central sources for media messages. Yet, computationally-constructed harms are an inextricable feature of contemporary dysfunction, with the internet and its facilitation of data extraction deeply enmeshed within destructive processes of surveillance capitalism, algorithmically-augmented inequities, and the persistence of colonial logics. 10 See Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2019); Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: NYU Press, 2018); Cathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (New York: Crown, 2016); Arun Kundnani and Deepa Kumar, “Race, Surveillance, and Empire,” International Socialist Review 96, no. 5 (2015): 18–44. To begin contending with these problems, this essay starts with the foundational rhetorics from which the present-day internet was developed. These examples will be examined to reveal assumptions of universalizing infrastructure and underlying developmental conceptions of ‘civilization.’ With such histories of technology often finding their origins in the United States and Europe, this essay invokes Brian Larkin in his desire “to discover where their insights have force and where their analytical assumptions turn out to be socially specific rather than universal to a technology.” 11 Brian Larkin, Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria (Durham, NC; London: Duke University Press, 2008), 15.

This essay operates in three parts. Firstly, it begins with a close reading of a scene from the 1972 documentary Computer Networks: The Heralds of Resource Sharing, which features the perspectives of computer scientists and engineers directly involved in the development of ARPANET. By analyzing this documentary scene by way of the art-historical reference it makes, we examine underlying ideals underpinning the ARPANET. Secondly, by examining the rhetoric of “resource sharing” for the network as universalizing civilizational technology, the essay threads through different ways in which the logics of coloniality underlie the internet. Lastly, through contemporary examples of web-based projects that seek to disrupt neocolonial logics, the essay considers how decolonial practices may emerge online, and possibilities for a decolonial web that refuses the extractive uses of data and reconfigures data as method for contending with the problems to be addressed.

Heralds of Resource Sharing

In 1965, while working for ARPA, computer scientist Robert Taylor initiated the funding of advanced research in computing at major universities and corporate research centers across the US. 12 Sergio Rajsbaum and Michel Raynal, “60 Years of Mastering Concurrent Computing through Sequential Thinking,” ACM SIGACT News 51, no. 2 (2020): 65. Often considered the technological precursor laying the technical foundations for the present-day internet, the ARPANET emerged from the activities of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) of the United States Department of Defense. The notion of “resource sharing” is articulated as the driving force behind Taylor’s development of ARPANET. 13 Rajsbaum and Raynal, 65. Here, “resource sharing” referred not only to dissemination of data over a network, but also served as a technical term referencing time-sharing practices as a method to optimize multiple users’ sharing of a computer. 14 Rajsbaum and Raynal, 65. For a technical definition of resource sharing, see also Michael A. Padlipsky, “A Perspective on the ARPANET Reference Model (RFC 871),” IETF, September 1982. “By ‘resource sharing’ we mean the potential ability for programs on each of the Hosts to interoperate with programs on the other Hosts and for data housed on each of the Hosts to be made available to the other Hosts in a more general and flexible fashion.” The term aptly appears in the title of the 1972 documentary focusing on the development of ARPANET, Computer Networks: The Heralds of Resource Sharing. Originally produced to demonstrate the ARPANET’s workings and capabilities for the First International Conference of Computer Communications held in Washington, D.C. in October 1972, the documentary was not completed in time, 15 Andrew L. Russell, Open Standards and the Digital Age: History, Ideology, and Networks (Cambridge University Press, 2014). but has since resurfaced online on the Internet Archive. 16 Peter Chvany, director. Computer Networks: The Heralds of Resource Sharing, 1972, 1:39 to 2:20. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/ComputerNetworks_TheHeraldsOfResourceSharing. The short film features internet pioneers such as Larry Roberts, Bob Kahn, and J.C.R. Licklider provides technical explanations of how the ARPANET functions.

Within the documentary, American engineer Lawrence G. Roberts speaks of computer networks as a universalizing infrastructure: Working at ARPA, Roberts asserts the necessity of a network like ARPANET in the dissemination of information, a form of resource sharing that leads to the formation of an advanced ‘civilization.’ Roberts identifies the issue of “small civilizations or small cities trying to develop separately and not having any way of sharing what they’ve learnt with other groups.” 17 Chvany, 1:39 to 2:20. He claims that “if that continues to happen, they don’t have a civilization.” Roberts argues that “the necessity was to provide a mechanism so that what was learned one place could be transferred effectively and directly to other places without re-doing it all and learning it all over again at each place.” 18 Chvany, 1:39 to 2:20.

Within this framework of information infrastructure, the dissemination of knowledge is entwined with the very foundation of ‘civilization.’ This follows a developmental logic: For one to develop as a ‘civilization,’ one must follow a predetermined trajectory towards a singular model of civilization often based on existing knowledge and structures of power. Even more striking is the image used in the documentary during this explanation: During Roberts’ interview, the documentary cuts away to the image of an engraving of William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, based on the 1771–72 oil painting by Benjamin West. As Roberts’ voiceover is delivered, the viewer sees close-ups of the engraving, their eyes guided across details of this image that depicts the meeting between William Penn and members of the Lenni Lenape tribe at Shackamaxon on the Delaware River.

West’s painting assumes canonical status in American popular culture, finding its presence in the pages of high school history textbooks to illustrate the nobility of Penn in his power to effect peaceful relations between Europeans and Native Americans. 19 Beth Fowkes Tobin, "Native Land and Foreign Desires: William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians" in Picturing Imperial Power: Colonial Subjects in Eighteenth-century British Painting (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 56. Through the portrayal of Penn and his associates in the act of bestowing gifts to the Lenape people, the image presents colonization as a benign and benevolent gesture that disguises political and economic power as advanced moral sensibility. 20 Tobin, 56. Central to the image is a bolt of cloth, the gift being exchanged for land, with the viewer’s eye then moving out towards the arc of Lenape people crouching around Penn, with light falling upon them in their feathered headdresses, beaded accessories, and elaborate clothing. Set up as a visual counterpoint to the Lenape people are Penn and the Quakers, portrayed somberly in darker tones. Here, they connote a rational and moral counterpoint as individuals led by radical Christian beliefs to peacefully negotiate exchange. 21 Tobin, 62. Penn’s outstretched hand not only emphasizes the gift exchanged with the Lenape people for land, but further signifies the creation of the colony and economic opportunity created for colonists in generations to come. 22 Tobin, 64.

Digital Colonialisms

While initially created to convey Penn’s highly developed moral sensibility, and by extension, the right to ownership over the land, the image is now critiqued for obscuring and excusing of later acts of betrayal enacted upon Indigenous people, after the Lenape were forced out of traditional homelands due to illegal colonial settlements. Instead of a magnanimous exchange, Penn’s ability to ensure peaceful relations must be seen in relation to the implicit threat of violence that suffused the European colonization of America. 23 Tobin, 62.

Through data dissemination’s entwinement with an image of colonial expansion and exploitation, the ARPANET’s development is imbued with troubling notions of a universalizing infrastructure that follows a developmental conception of ‘civilization.’ In this sense, it is ‘universalizing’ as a system that moves towards negating differences across contexts, with aims of achieving a singular vision of an often-Western notion of modernity that is assumed to be more advanced, and thus universally beneficial. When seen in relation to the idea of “resource sharing” through the ARPANET, the dissemination of data cannot be seen as a benevolent exchange. Rather, it foregrounds ideas about information infrastructure as a ‘civilizing’ tactic that operates over existing inequities. It is here that “resource sharing” and computer networks are imbued with a colonial dimension. Such a relationship between data, the internet, and coloniality that has been noted by artists, activists, and academics.

The artist Keith Obadike points out the “odd Euro colonialist narrative that exists on the web […] there are browsers called Explorer and Navigator that take you to explore the Amazon or trade in the ebay. It’s all just too blatant to ignore.” 24 Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 106. While colonial dimensions of the internet may function on this semiotic level, the relationship between information technologies and colonial processes of extraction and cultural displacement have also been analyzed in relation to broader political realities. This has previously been articulated across time through terms such as data colonialism, digital colonialism, cyber colonialism, and technocolonialism. 25 See Jim Thatcher, David O’Sullivan, and Dillon Mahmoudi, “Data Colonialism through Accumulation by Dispossession: New Metaphors for Daily Data,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34, no. 6 (2016): 990–1006; Michael Kwet, “Digital Colonialism: US Empire and the New Imperialism in the Global South,” Race and Class 60, no. 4 (2019): 3–26; Thomas L. McPhail; Pinar Tuzcu, “Decoding the Cybaltern: Cybercolonialism and Postcolonial Intellectuals in the Digital Age,” Postcolonial Studies 24, no. 4 (2021): 514–527.

In 2016, Jim Thatcher, David O’Sullivan, and Dillon Mahmoudi critiqued the excitement around ‘big data,’ arguing that the extraction and collection of personal data was “a form of capitalist expropriation and dispossession.” 26 Thatcher, O’Sullivan, and Mahmoudi, “Data Colonialism through Accumulation by Dispossession,” 990–991. They proposed the term “data colonialism” as a means of articulating the asymmetry of data capture by big tech companies such as Facebook. 27 Thatcher, O’Sullivan, and Mahmoudi, 990–991. Similarly, using South Africa as a case study, Michael Kwet proposed in 2019 that the United States re-asserts coloniality in the Global South by dominating the use of digital technology, enacting “digital colonialism” in exercising the imperial control of software, hardware, and network connectivity. 28 Kwet, “Digital Colonialism,” 3. The term “digital colonialism” was previously invoked during discussions in 2017 about Facebook’s Free Basics, the platform’s free and limited internet service for markets predominantly in the Global South. Ellery Biddle, advocacy director of Global Voices, argues that:

“Facebook is not introducing people to open internet where you can learn, create and build things [...]. It’s building this little web that turns the user into a mostly passive consumer of mostly western corporate content. That’s digital colonialism.”

29 Olivia Solon, “‘It’s Digital Colonialism’: How Facebook’s Free Internet Service Has Failed Its Users,” The Guardian, July 27, 2017.

Meanwhile, in Pinar Tuzcu’s analysis of the 2018 Cambridge Analytica data scandal, “cybercolonialism” is used to describe how knowledge production in the digital age creates new colonial relations. 30 Tuzcu, “Decoding the Cybaltern,” 514–527.

A Decolonial Web? Migrant Death Map as Case Study

Terms such as “digital colonialism” foreground the internet’s ability to facilitate resource extraction or exploitative labor practices enacted under global capitalism, emphasizing that information infrastructures are ultimately able to reproduce the coloniality of power by exacerbating existing inequities. In this sense, “resource sharing” as an ideal is conceived on uneven topographies, and while conceived as being beneficial to communities, ends up privileging existing structures of power. Given the continued manifestation of colonial logics through the internet, this essay re-centers decolonial studies in the desire to engage with possible practices in addressing the colonial dimensions of the internet. Here, the decolonial approach serves as an “instrument for transforming the world by transforming the way people see it, feel it and act in it.” 31 Madina V. Tlostanova and Walter D. Mignolo, “Global Coloniality and the Decolonial Option,” Special Issue, Kult 6 (2009): 131. Rather than identifying “the object or objects to be studied,” the decolonial option places emphasis on the “problems to be addressed.” 32 Tlostanova and Mignolo, 131. These problems emerge from what Mignolo and Tlostanova identify as the “modern/colonial matrix of power,” with coloniality both an historical and extant force that persists and underlies the very conceptions of modernity. 33 Tlostanova and Mignolo, 131–132.

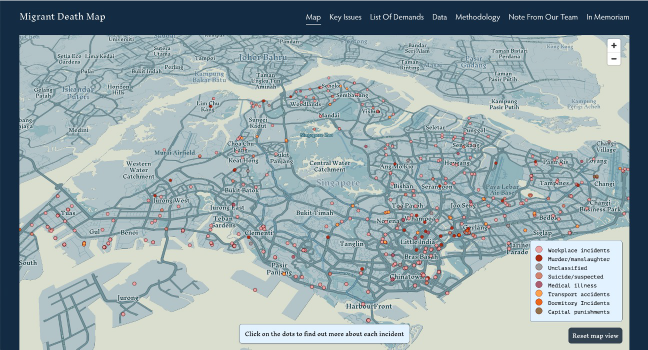

The essay turns to the context of Singapore, a highly-networked city enmeshed in the global politics of contemporary data flows. As a wealthy postcolonial nation that is simultaneously complicit in extractive uses of resources and labor from neighboring contexts in Southeast Asia, East Asia, and South Asia, examples of online data-based projects like the Migrant Death Map offer examples in using data for contending with extractivist or neocolonial logics.

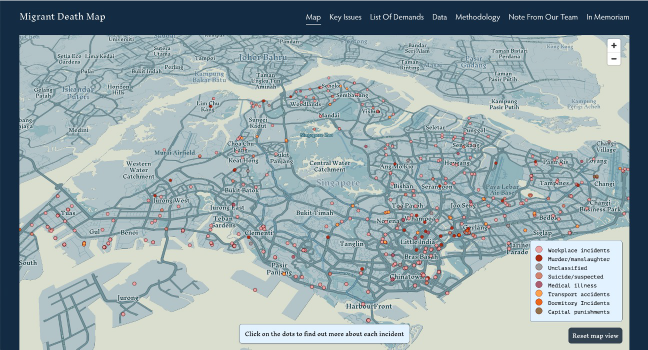

The Migrant Death Map is an activist website that aims to analyze “precarity, violence, and disregard for migrant life in Singapore.” 34 “Migrant Worker Death Map,” Migrant Death Map, 2022, https://www.migrantdeathmap.sg. Harnessing publicly available reports about the hundreds of deaths of migrant workers in Singapore from January 2000 to August 2022, the site collates usually occluded or dispersed data about migrant deaths in newspapers and reports, highlighting the lack of easily available government data on migrant worker deaths. 35 See “List of Demands,” Migrant Death Map, 2022, https://www.migrantdeathmap.sg/list-of-demands. “Current and readily available datasets are very limited, often aggregated at levels that are too general to enable detailed meaningful analysis, or lacking in scale and comprehensiveness.” The Migrant Death Map team collaborated with digital storytelling firm Kontinentalist to visualize the large amounts of collected data on a geographical map of the country, pinpointing sites of reported incidents as color-coded nodes. By transmuting these reports into easily accessible data in the visual form, the project is careful to assert that “migrant workers are more than data points,” 36 “Migrant Workers are More Than Data Points,” Migrant Death Map, 2022, https://www.migrantdeathmap.sg/morethandata. illuminating the interior world of migrant workers through video interviews that are also published on the website.

The website lists the key issues that migrant workers face, spanning abuse and unsafe workplaces, presenting a list of demands proposing possible solutions. For instance, on the issue of data transparency surrounding migrant deaths and accidents, the Migrant Death Map team makes demands for publicly available data points on incidents, requesting for specific information such as names, nationalities, ages, industries, worksites, penalties issued, compensation received, and follow-up actions. 37 “List of Demands,” Migrant Death Map, 2022, https://www.migrantdeathmap.sg/list-of-demands.

The Migrant Death Map is reflexive of its use of familiar colonial tools such as the archive and the map, but resists their limitations and expands such tactics in deploying them as a long-form multimedia piece to build what the team describes as an “alternative archive of stories and experiences that have not been verified or validated by news media.” 38 “Note from our Team,” Migrant Death Map, 2022, https://www.migrantdeathmap.sg/note-from-our-team. The Migrant Death Map’s tactics may be seen as an instance of “counter-cartography,” a practice emerging from multiple traditions from the arts, academia, and political activism. 39 Severin Halder and Boris Michel, This Is Not an Atlas: A Global Collection of Counter-Cartographies (Verlag, Bielefeld: transcript, 2018), 13. Described as “a political practice of mapping back,” counter-cartography melds mapping practices with theoretical critique. In the context of the Migrant Death Map, it is through the painstaking collection of obscured data and the re-acknowledgement of the meanings that have been hidden that the lives of migrant workers are mapped and made tangible again, in spite of the lack of government support or biased reporting from state-controlled media. To invoke Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein in Data Feminism, this is a counter-cartographical practice that maps and creates space for an attunement to the “bodies uncounted, undercounted, silenced.” 40 Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein, Data Feminism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020), 21.

The case study of the Migrant Death Map demonstrates several tactics for possible routes towards decoloniality through the internet. In the disruption of extractivist logics towards labor, the first tactic involves the seeking out and reclaiming of occluded data, of the information missing from datasets, and making such silences legible once more. The second observable tactic is the use of a longform and multimedia approach, one that complicates the colonial possibilities of the map and the archive. By fleshing out the internal lives of migrant workers through audiovisual material, the Migrant Death Map resists the reduction of human life to data points. Lastly, the tactic of clear, actionable demands based on the careful parsing of data ensures identifiable pathways towards justice for migrant workers.

In this manner, the Migrant Death Map enacts a vision of a decolonial web through its repurposing of data, its emphasis on the problems to be addressed, and its strategic disruption of logics of extraction through web-based platforms. If the modern foundation of knowledge is territorial and imperial, counter-cartography posits the tactics for refashioning these territories into spaces wherein the silenced are made tangible one more. While these practices do not contend with the full injustices enacted, facilitated, and exacerbated by the uneven topographies of the internet, they provide us tactics for envisioning a decolonial internet and reclaiming data.