PAOLO CIRIO, on capturing the dangers of facial recognition technology

by Kristin Eichenberg

Paolo Cirio is an Italian artist, activist, hacktivist and social critic whose artworks lie at the intersections of legal, economic, and cultural systems of the “information society”. Cirio’s artworks and political activism question uses of invasive technologies and challenge the ethics of data, privacy policies, and violation of related civil liberties in the United States and Europe.

My conversation with Paolo will demonstrate the critical role artists take in social activism, using tools of visual language to aid public understanding of these complex issues and concepts within the topic of dark data. Cirio’s body of work disrupts digital domains and public spaces, to advocate for transparency, more ethical data policies, and critical reform that will provide individuals with autonomy over their digital footprint.

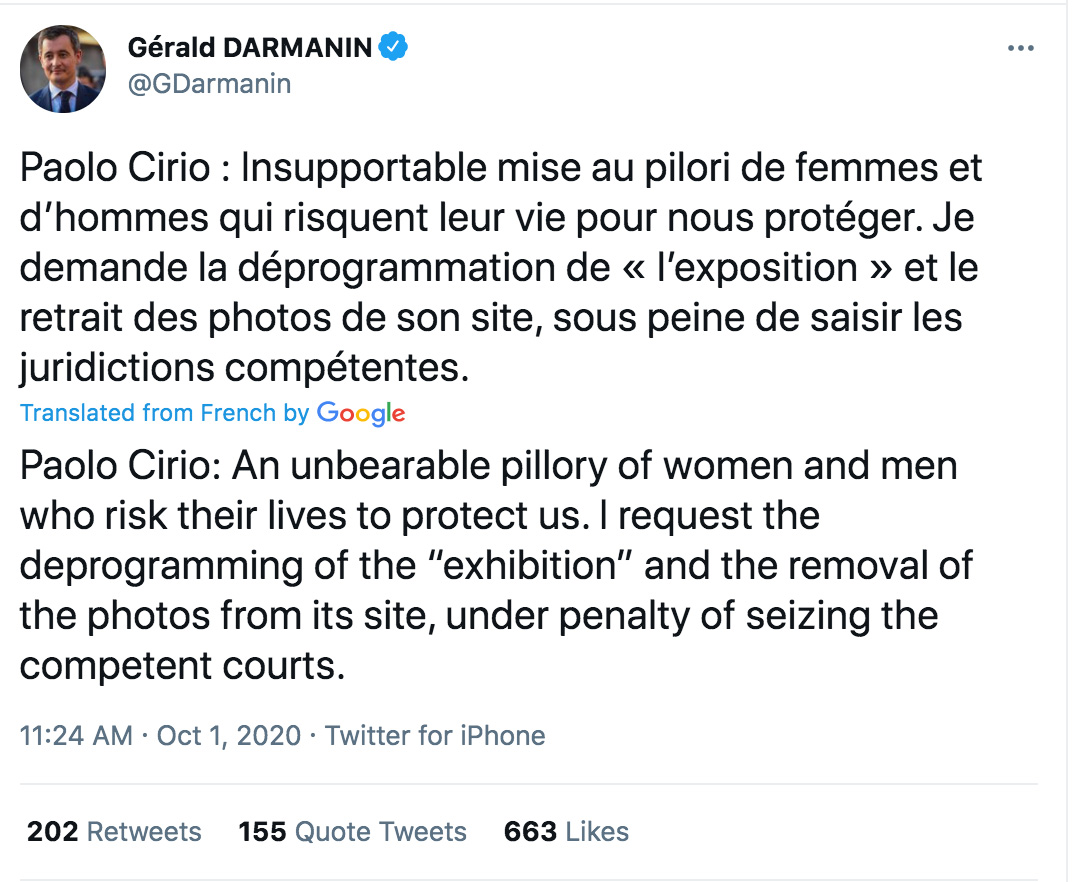

In his latest project, Capture (2020), Cirio published a collection of 4,000 photos of French police officers online and in a museum exhibition in Lille, some of which were also wheat-pasted out on the streets of Paris. Cirio created the database from publicly-sourced photographs taken during protests, which he then processed through facial recognition software. After crowdsourcing their identifications on a public website he launched titled, “Capture-Police.com’’, France’s Minister of the Interior, Gérald Darmanin, threatened legal action against Cirio and publicly tweeted for the site to be removed along with the entire exhibition.

Perhaps most noteworthy in the collection, was photo evidence of seven officers that were pictured unlawfully shooting at protestors; further illustrating the need for citizens who are constantly surveilled, to point an eye back towards those watching who are legally protected with more violent means of power. Cirio clarifies that his main message is to highlight the asymmetrical power in law enforcement’s use of biometrics with facial recognition software; by reversing this dynamic, the work concludes that facial recognition is dangerous for every citizen, even the police, who in fact attempt to hide their identities from the public.

Accompanying Capture, was a campaign introduced by Cirio to ban facial recognition technology in all of Europe, which received 50,000 signatures and merged with organizations for european digital rights network and the campaign ReclaimYourFace. These initiatives promote the prohibition of indiscriminate or arbitrarily-targeted uses of biometrics, as this establishes even more oppressive means of mass surveillance and violates our basic civilian rights.

In the following interview, Paolo and I discuss why an absolute ban of facial recognition is necessary, along with the response he received from Capture, how he navigates the legal frameworks in his work, and the emergent issues with facial recognition as it trends towards behavioral and psychological profiling of mass populations.

[ You can read more interviews with Paolo Cirio on Capture, as well as view the complete archive of his past projects and research on the artist’s website. ]

Kristin Eichenberg: Can you begin by introducing how this project, Capture, began?

Paolo Cirio: The project Capture started in 2019. I was invited to produce a new project in France by a university close to Lille. I was under pressure to come up with something, and in my research I found that in France, the police use facial recognition for surveillance. That was very surprising to me, because after so many years living in the U.S., I thought Europe was more advanced for regulations of that sort. I found this was not only the case in France, and all over Europe.

At the same time in France, there were quite a few cases of police brutality. As a European activist, I understand the social context of France, and I’ve experienced being in some of those protests, and so I connected those points and slowly came up with this idea. So I started to collect those pictures of protests in France over the past few years, from 2010 to 2020.

KE: Oh wow okay so the collection has been going on for quite a while.

PC: Yes, because the methodology, if you will, was just going to google and searching for protest photos with the key words: “Protest” “France”. Google was giving me as a result, any kind of pictures with police – then also keywords, “police” and “French cities”. So it was unfiltered, pretty much, and I basically downloaded all of the pictures Google was giving me, sorting them only by city and year.

Then, as a coincidence, friends of friends connected me to actual activists – citizen journalists– basically photographers that had a press pass to attend these protests and take pictures with their own cameras. In that, I acquired quite a lot of pictures in much higher resolution as you can imagine. That took a few months working these photographers, and at the end of the day I had about 1,000 pictures that showed police officers during protests in France.

KE: So in these 1,000 photos you had first acquired, you then had high resolution photos of these police officers’ faces that couldn’t be found on google, so that it was possible to run them through facial recognition software?

PC: Yeah, well then I ran them through facial recognition software– a very basic one– since, in each of those pictures, there could be one or more than one police officer, the facial recognition software was capturing – or cropping– only their faces.

In some cases, even in the high resolution photos, if the officers were far away, then the resulting photo was low res, very few pixels. But because the software is so powerful, it could actually find just one eye and a nose. So there was a second process I did manually, to remove all of the pictures that were too low res like this, where you could virtually not even recognize a face – only the software could recognize the face. So there was quite a bit of manual work in the process, and nevertheless to remove all the protestors, or civilians, before running through the software.

All of those pictures were taken in public space, true, but they were also sometimes taken inside of police cars, so it’s questionable how much that was public space. Let’s say about 50 percent were taken from newspaper articles, then the others were taken by these photographers who had pseudo-permissions to do so.

Legally, or what a lawyer would say, is that any picture taken at a public event, belongs in the right to inform the public. If you’re just walking the street, and doing something private, it’s questionable if a photojournalist can publish that picture, but if you’re at a protest in a public event, you’re aware of joining a public event, and so all that material information about that public event should be public, and journalists should be able to report on it and publish that material.

So that’s why I was legally allowed to do this project. Of course, then it really depends where that picture was captured – you can imagine, with this amount of material, I couldn’t know exactly where each picture was taken– if it was too controversial, private, or public.

KE: I had read your interview with Hyperallergic, that noted how this project mimics the tools used by data analytic companies such as Clearview AI, who scrape public images that are circulating on the web and are known to provide facial profiling services to law enforcement agencies.

PC: I was definitely aware of Clearview AI; what they did and how they did it. It was meant to mimic something similar, but applied to identify law enforcement and the police. The way it was done was similar, true; but with less data and not by processing facial biometric data. If I could have spent more time searching on google and with artificial intelligence software, I would have eventually reached the same amount and accuracy.

Nevertheless, the amounts here are all relative – I published 4,000 faces, and Clearview AI, I don’t know how much they claim to have, a huge amount– millions. But in my case, this was an artistic preference of provocation to make a point. So if I had 5,000 or 10 million, it doesn’t change the message.

KE: So what’s your response to Clearview’s legal argument that their right to capture biometric faceprints from our online photos are protected by the First Amendment?1

PC: The fact that they claim they’re using freedom of speech to harvest this data, is their own personal claim. Legally in the U.S., scraping social media for data, is still up for legal debate now and in some cases is actually permitted. There’s also a question of how much commercial interest there is, how much of an invasion of privacy this is, but definitely the claim of using the first amendment is an underlying argument for most of these companies. From Facebook to Clearview AI, and many other ones, that’s been present in the United States for a long time.

KE: When I was reading Clearview AI’s defense statement in their initial lawsuit with the ACLU back in 2020, it was infuriating to see how easily they claimed their first amendment right to freedom of speech by way of simply operating on the public domain of the internet – and further, for them to then argue that things like BIPA (Biometric Information Privacy Act) is violating their Freedom of Speech. They subliminally blame the general public, as if to say, “it was in your own freedom of speech, to have put an image of yourself online in a public domain, and therefore it’s within our freedom of speech to use it” and then scan billions of images for biometric data just because general communications on the internet are protected by Free Speech. It’s crazy that their extreme violation of privacy can even be claimed as “speech” when they are profiting off of collaborative efforts with law enforcement and abusing the expressions that the First Amendment was intended to protect. It’s really problematic.2

PC: That’s usually the first argument of defense in these lawsuits, including in the lawsuits with Trump – the misinformation sagas that have been happening the past few years. I think that the protection of the first amendment is great, but in the United States there’s quite a bit of confusion in using it to defend any type of argument,finally that’s changing very fast.

After four years of Trump spreading misinformation and especially now that he lost the election, and with the recent attack on the capitol, that interpretation of the first amendment really changed. And now, he’s not even able to run his own app for the far-right (after being banned by twitter), which is a radical thing in the United States. To tell someone to not even create a new technology and a media outlet, is a really radical thing. It’s a legal concept around freedom that finally changed.

I think the difference between the US and Europe, concerning the notions of free press and free speech, is the fact that here in Europe, we had fascism and nazism. So after the second World War, we did apply laws that allows free speech and free expression but within limits and ethics, forbidding hate speech connected to fascist and nazi propaganda. These are historical facts that didn’t happen in the U.S., until recently…

KE: Hate speech is often protected by the first Amendment in the U.S., and censorship now, continues to be such an issue in trying to protect these rights at the same time as fighting against their abuse.*

PC: True, I mean these things are very complex issues. But it’s definitely a matter of historical evolution, a cultural development, that the U.S. finally experienced. Not to mention that the Internet is a very recent media and we are just barely learning how to apply ethics to it.

In this particular case, it’s not just about content moderation but it’s actually about the technology itself. Because free speech usually discusses the message, the communication, while in this case the technology, the tool – Clearview AI– says that because of free speech we can run our platform and our technology under this protection, which makes no sense.

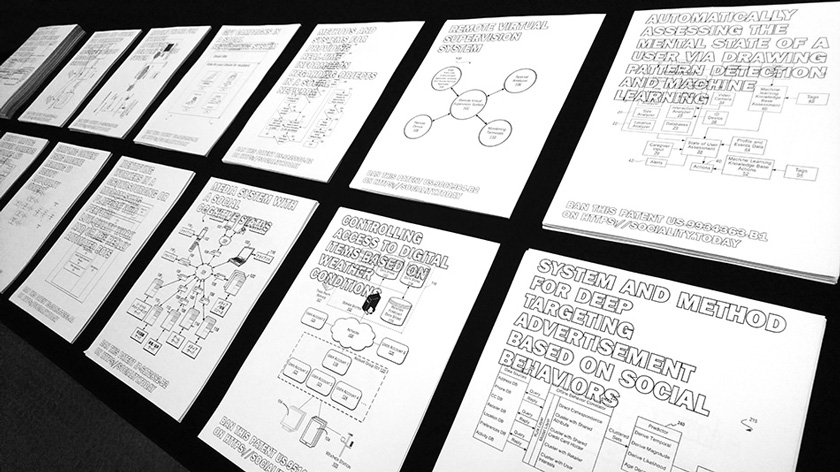

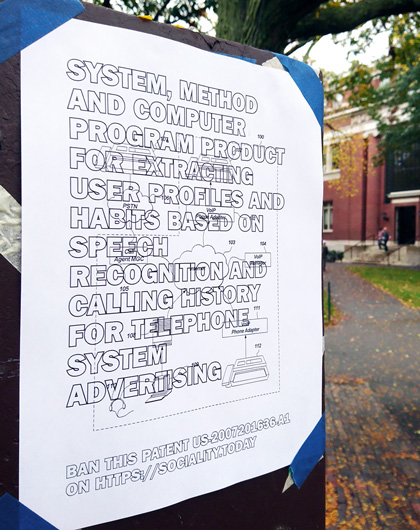

This is a legal conception that technology has no social implications, so it doesn’t need to be regulated or banned, and this idea is connected to my other project, Sociality, where I suggest to ban patents of manipulative and invasive technology. We always thought– ok, technology could grow and develop freely, because it’s part of innovation, and the freedom to innovate, but now it’s not exactly like that.

KE: So then with facial recognition technology, why, in your opinion, is a total ban of this technology across Europe necessary, rather than imposing regulations and revising legislation?

PC: So regulating facial recognition was a discussion when I was sharing this idea with other partners and privacy organizations here in Europe. Some of them told me it may be too radical to ask for a total ban of facial recognition, and that we might lose some support – and actually, because of that, some organizations didn’t join. To me, it was absolutely necessary to promote a total ban of facial recognition because of the dangerous that it can collect this biometric data from a device that, today, may seem fine, or non-dangerous, but in the future, might leak that biometric data, which might ends up in some other hands and used to match the identity of individuals. We should be already aware of how often these leaks happen, and with biometric data it is even worse.

Some people might say to me, like in a youtube comment, “Oh but biometric data can be stored in a safe place.” I actually don’t believe that, because biometric data is a bit of data that at one point, is not always encrypted, and can end up with some bad actors.

Well you may have it now in your iPhone that you trust, but it’s also starting to be used for door locks – that is biometric data of your face that is stored, for how long, no one knows. Tomorrow, that can be hacked or sold to another company, that can be like Clearview AI, and it’s associated with your name and your personal life. So that bit of personal data, in that biometric data, can follow you for the rest of your life. Simply because the biometric data doesn’t change over time- meaning that your face is recognizable by Artificial Intelligence from when you’re a small kid, to when you’re old.

KE: So age can be traced? The technology can match your biometrics from a younger age to biometrics that may be collected when you’re older, and make that match over time?

PC: Right, yes, over time it can always find you and identify you.

KE: I didn’t know that…

PC: Well, unless you are completely changing your entire face.. but yes, that’s the scary part. And some people don’t think the data of how we look is that dangerous, but all biometric data is that dangerous, also your fingerprints are not changing over time. The difference though, is that your fingerprints aren’t exposed as your face.–

KE: You have to actually give permission, you have to give consent to have your fingerprint stamped.

PC: Right, but those are not detectable with that from a distance. Instead, your face is something that sooner or later, you have to uncover, even if you wear masks.

KE: Good point. I was curious what you thought about developing more approachable and wearable forms of biometric camouflage to potentially combat this exposure while we remain unprotected in public spaces…but that idea just seems more futile when discussing what’s already been captured.

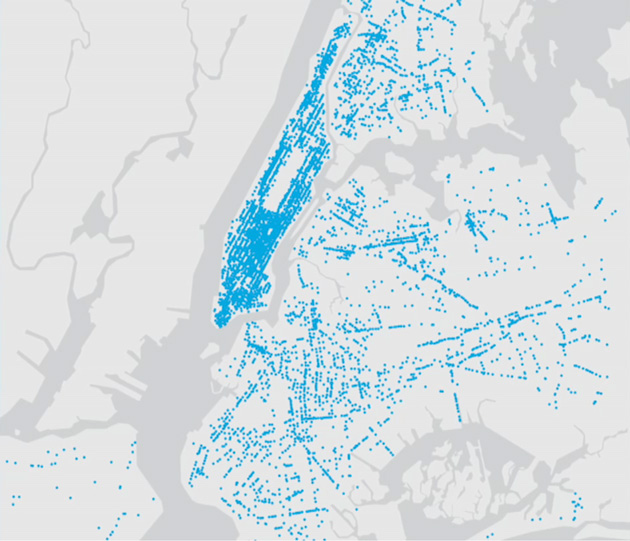

Your comment about how long this type of data is stored has me thinking about structures like Link NYC and all the gaps that exist in their privacy policy.

As you know, there’s thousands of these Link NYC digital kiosks all over the city that replaced the old phone booths. Of course, they’re all equipped with cameras as well as “environmental sensors” , which we can all imagine, means they’re capable of audio recording too. Technically, the footage and data in these kiosks can’t be arbitrarily accessed by law enforcement unless it relates to a criminal investigation – but in addition to the issue that these kiosks are fully equipped surveillance machines, LinkNYC’s privacy policy is also subject to several other privacy policies from parent companies, and indicates that the collected data and footage can be stored for several years…there’s no real transparency.3

PC: Yes, and there’s all these private contracts, and those contracts are very complex, that are still general enough to allow sales to data brokers. It’s a huge market, especially in the U.S. And so my fear, the reason I think it should be banned completely, is because in 10, 20 years, we don’t know which kind of government we will have, and what that data will be used for. And by banned completely, yes, I really mean the biometric data about the face, specifically, should not be collected and processed for identification and classification, because facial recognition technically works in four phases, let’s say.

The first is just the detection of the face, which is something I’ve done for this project. Just the detection of the face, is an algorithm that’s in all cameras today. Then the second is the biometric data extraction from the face, which are just data points of your face. Then there’s another algorithm that will do the matching of that data with another face, or to a sample, to determine things like, how young you are, what your gender is, if you’re gay or not…then there is a final step, which is to connect that set of data to an actual person, their name and surname, where they live, what their occupation is, and so on.

So I mean, facial recognition needs to also be broken down in those steps. Because until you do the last step, you just have data about a face without a name and a surname, so it’s almost useless, although it can still be used to discriminate. That’s why I’m saying with this project, that banning facial recognition is particularly about using that data for identification and classification, which is the most dangerous part of facial recognition. Because otherwise, have facial recognition inside a camera is harmless, until you use it for classification, which means discrimination bias, or identification, which means surveillance and invasion of privacy.

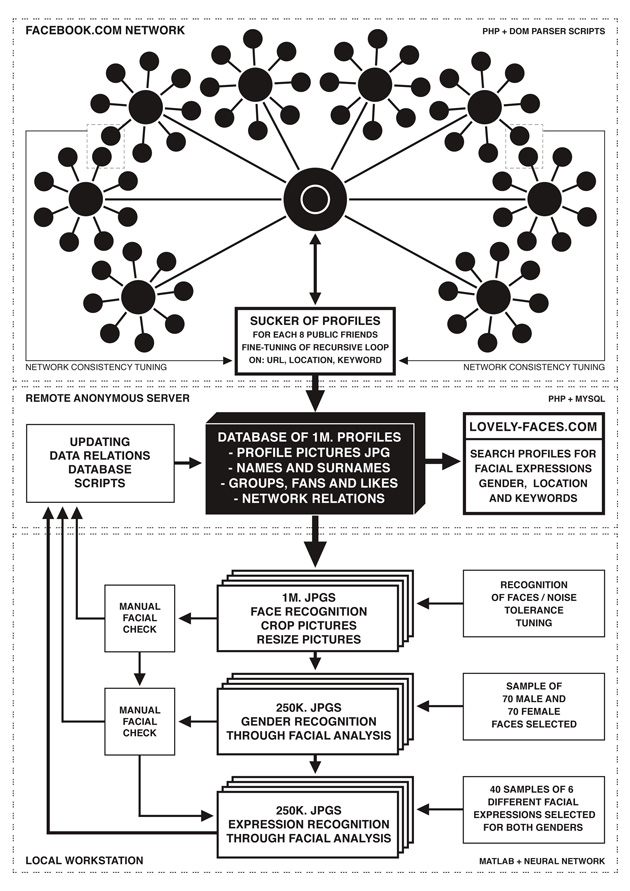

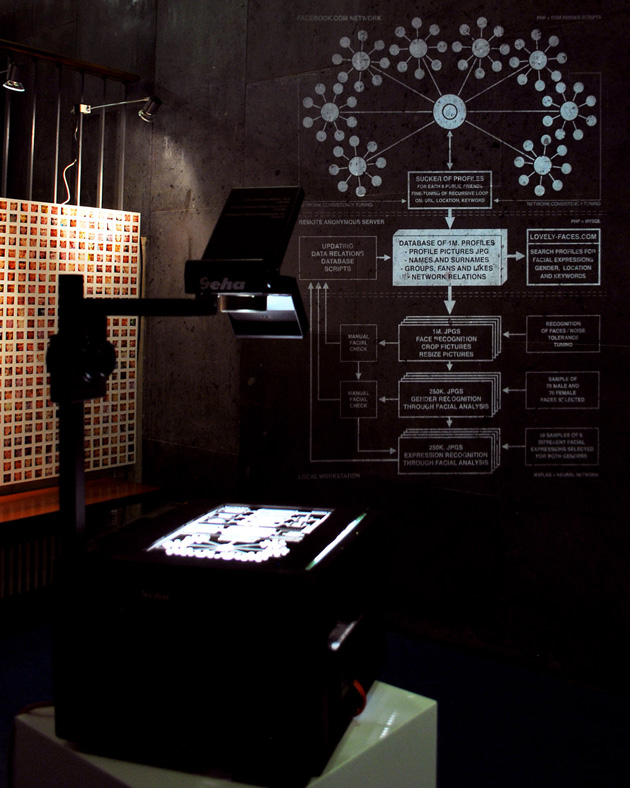

So with Capture, actually, I only did the first step and the last step. I didn’t take the biometric data, I didn’t extract the biometrics of these faces and try to match that face with another face to figure out who they are. That’s something I’ve done with another project, Face to Facebook, 10 years ago.

Yet with the project Capture, I’ve done the most dangerous step: trying to identify the agents by allowing everyone to type in their name, adding the last piece of the chain of information missing. Which is why it generated these strong reactions. After one day of the publication of the project and the press release, the French police unions started to complain, and the Interior Minister of France began tweeting about it.

KE: What sort of events took place when Gérald Darmanin threatened legal action against you, and what was the aftermath of that?

PC: Well that was very quick, his reaction, because he knew the institution that helped me to produce this work. So he was actually very close to this project. He’s also the “boss” of the police force in France. The Interior Minister here means that’s the minister of the police, literally. Randomly, a weird coincidence in this, is that he also used to be the mayor of the town of the university where I developed this project. The fact is, he was forced to act by the police unions, which in France, are very influential. So the police unions were the first to react; they phoned up the minister, and he saw that it was going on in his town and had to do something.

At that point, I didn’t do anything. I was amazed by the reactions and kept my nerves and waited. Then the institution, where the project was also planned to be shown after a few days, published a press release to the journalists – not even to me, directly– taking distance from me… they said, “We don’t know what he’s doing, we don’t like what he’s doing, he breached a contract with us”, all stuff that wasn’t real.

Basically, they left me alone in this situation. At that point, I said, okay it’s getting too risky, and I took down the website Capture-Police.com which was the most controversial element of this project, because that’s where there were all 4,000 pictures of the faces, where people could actively tie the name of the agents if they knew it to the picture.

Of course, everyone could write whatever they wanted. So that was just a provocation for me to push to that point of upsetting the police. And to me, worked very well of course, because it was meant to generate harsh reactions, but not to this point to get censored.

KE: Well what’s interesting too, with the crowdsourcing identifications for the police officers, is considering the inaccuracies in that process, and the same can be said for how biometrics are used by the police themselves in identifying suspects.

That’s a huge concern for the entire public; that they use this technology that’s inaccurate, with racial bias embedded and coded into it… they could assume the right themselves to arrest anyone just with a biometric match that’s completely inaccurate.

Do you know when the French police started using the software explicitly?

PC: Well in France, the police have particular powers because of the terrorist attacks that have been happening in Paris and all over France. They have a few units for mass surveillance, and that’s why they’d started to use facial recognition. A few years ago when I started this project, there was even a plan to use facial recognition for a National ID. So we’re talking about a time when this was still an exciting thing. There’s always a time when new technology is just exciting, and everyone is talking about it in a positive way. Then after a few years, or months, you start to see the dark side of it.

When I started this project there were critics about facial recognition of course, but there was also a lot of excitement. That’s also why we still have facial recognition on our phones, and we might not see it again in a few years…

The police in France were able to use it because of loopholes here with the local and european political structure – it’s a bit complicated– but the European laws can block national laws or the other way around, like the federal structure in the U.S.

KE: In the U.S. there’s the CCPA (California’s Consumer Privacy Law) and the Virgina Data Protection Act, which draw many comparisons to the GDPR, but American’s are pushing in the direction of federal regulations for data privacy.

But is this the best route to go? I mean, if we just apply more fines with Federal Regulation to the data breaches that will take place, Big Tech would be able to circumvent these things easily and pay their way out of everything.

PC: So the situation in the U.S. is that there is an agency that should do this job, the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) and they do deal with privacy issues nationwide, however the problem with the agency is that they have no real enforcement powers. They can’t actually even fine companies directly.They can only issue some forms of complaints and suggest regulations to the Congress , and yet that’s the only nationwide agency that actually deals with these things.

Nevertheless, because it’s a federal agency, every four years they change directors. So they’re highly influenced by these political wings – Also Trump did change the director – but even if they are inclined to do something about these privacy issues in the U.S., they don’t have much power, by design.

While in Europe we have several regulatory structures. That’s why we have the GDPR in Europe; we have several agencies only focused on privacy and data protections. Some of these legal structures do have enforcement powers and rigid regulations like the GDPR. In the U.S. instead, so far these regulatory initiatives are only advanced by Individual States –by California and New York State –they’re great, but they’re kind of weird if you know the back story.

So there’s some stories with these – In the other campaign I was running for the Right To Be Forgotten, in the United States, after some years I was approached by legislators in New York State that told me, “Oh, we should work together, we really want to pass this bill in New York State about the right to be forgotten..”, however they were basically wealthy private individuals asking me to raise money to pay a lobby firm to pass a bill. This is how policymaking in the U.S. really works, with expensive lobby and influence by the wealthy leveraging grassroot organizations. It’s backward compared to Europe.

KE: The story about the CCPA? What happened?

PC: There was this real estate guy – I think in the San Francisco Bay area– a very rich guy that happened to have a friend that was working at Google. They went to dinner together – it sounds funny but it’s really true – and at dinner the friend from Google said, “Oh we know everything about you…no, we know everything about you!”

So he got upset and started to figure out how much they know, and so he started – from being a real estate guy– he started a lawsuit against Google. Google put out all their lawyers– picture how big those lawyers are– well he paid other lawyers, and they kept going to the point where that guy started to campaign in California to pass this bill. That wasn’t an organization, that was a wealthy individual. You can read this back story on a famous NYT piece.

KE: Wow, and just a real estate agent.

PC: Yeah and I don’t know the history behind the New York one, because it’s more recent. Those bills are great, but still the problem is that the approach is State by State, which makes it very complex in the United States.

KE: If I recall correctly, in the proposed legislation for the NYPA, there’s a section that states an individual whose privacy has been breached has the right to sue the company. So I’m just imagining how some people, like these hedge fund guys, could take advantage of this and easily file an individual lawsuit against a small company, hurting our small businesses.

PC: True

KE: Perhaps if we had a larger structure on the federal level like the GDPR, it would, hopefully, have better protections for the small guys. Currently, legislators in the United States are proposing that better data protection can be developed by adapting the model of the “Information Fiduciary” which would act as a legal holding trust between an individual’s personal data and private enterprises who request it’s use.

From what I’ve read so far, the idea is that smaller business entities would be exempt from this rule, and to require larger entities including search engine, ISP’s, email providers, cloud storage services, social media, and online companies that track user activity, the “duty” to protect their customer’s information, so that it’s not used against the individual’s best interest. Just like how it works in the relationship between doctor and patient, attorney and client…

PC: I’m not as familiar with this, it’s kind of recent and gets very complex. But to me, it sounds like a commercial law solution to an issue that instead, is more of a civil right issue. So the idea of an Information Fiduciary, where you have a trust between a company and the consumers, looks like a private contract, which is why I mentioned “commercial law”. Under that contract they have to include clauses that protect the privacy, or give rights over personal data to the consumers; however that’s still a private contract, that in the U.S. is very complex, or I should say, much more in defense of the companies, and not the consumers.

So I would say that’s the first problem, and the main problem is that there are not many consumer rights in the U.S. In that case, a private contract of that sort between consumers and the company, would yes, defend the rights of a consumer, but only to the point of that contract, which also allows the company to find loopholes – commercial loopholes– to use and abuse data in other ways.

Definitely, of course, there should be more civil rights, if not human rights, as protection from this abuse of private data, and not be made into commercial issues. Something this also connects with, is the credit score in the United States. The credit score is very similar to the social score in China, if you will -

KE: Right, but opaque vs. transparent

PC: Exactly. In the 1970’s, there was a reform made to the credit score in the United States, the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), that allowed consumer citizens to have agency over their credit score after a few years. Meaning, by national law in the U.S. after a certain number of years, you could even erase all your past data about your score, which to me, seems like the right approach.

This reform of the 1970’s shows that in the United States, there have already been cases, and laws, that allow this to happen – it’s not impossible– to protect consumers to that degree, in terms of privacy and especially in terms of discrimination. A bad credit score, doesn’t allow you certain services, like welfare, etc.. so it becomes a form of discrimination in that way.

So that seems the best approach, not only in terms of privacy, which in the U.S. is maybe not that well defined as a cultural notion, but through this lens of discrimination. Because discrimination laws in the U.S. are pretty strong, companies and institutison have to follow them quite strictly.

If there was this type of approach to the data and technology world, that, I think could even work better than all of these privacy acts and state initiatives to protect privacy. We’re probably not far from that actually, because facial recognition for instance, is prone to discirmination and bias a lot. So if that is seen as a machine of discrimination, rather than only a machine of surveillance – because you know in the U.S., some people might like surveillance.

KE: Yeah true, I mean taking the pro-surveillance argument, it’s prevented several terrorist bomb threats. That’s so interesting to suggest applying Discrimination Laws to technology itself, how it’s deployed, rolled out and especially how its tested, as the tech is so often tested in low-income, marginalized communities.

It’s great that public awareness of data privacy issues, especially with all these documentaries that are out, is growing. There’s always been a sense of paranoia too, about technology like this, at least I’ve definitely noticed it in my generation. I wonder how the public would react in a scenario where facial recognition didn’t exist, what that would even look like, I guess.

PC: I think we wouldn’t even notice…

KE: People wouldn’t have their face filters… I mean if something like facial recognition was completely omitted… it seems like we would only notice small pleasures like that, and some conveniences in our lives, gone. I’m just thinking in comparison to China, how they can use their biometric face print for so many things; to pay for things, their ID, just more use of facial recognition when they’re out in public. Since we’re not to this point yet, it makes me wonder if it was gone now, how much we would even miss it in terms of being functioning citizens.

PC: There’s also a lot of cultural norms embedded in that, in the acceptance of certain technologies. We might become used to something or become dependent on something, I mean we’re totally dependent on social media whether you like it or not. Facial recognition in my personal life, I don’t use it, so I wouldn’t even notice if it disappeared. But in China, yeah it’s already that level of dependency, simply because it allows access to services.

KE: Now it’s like there’s this social conditioning through things like instagram, to be obsessed with seeing ourselves through face filters- and how people interact with each other socially and communicate through these things- that if it were taken away, it would be the people fighting to get facial recognition back because they want a face filter- something so arbitrary and unimportant.

PC: It became a tool to communicate…

KE: It became an addictive tool…

-

As Judith Butler states in the opening remarks in her text, Burning Acts: Injurious Speech, “the Supreme Court has reconsidered the distinction between protected and unprotected speech in relation to the phenomenon of ‘hate speech.’”— In one of the cases in question, R.A.V. v City of St. Paul, in which a white teenager was charged with injurious speech for burning a cross in front of a black family’s house, the Minnesota State Supreme Court argued that the act of burning the cross is not protected speech as it constituted “fighting words”. — Ultimately the United States Supreme Court reversed the state’s decision, reasoning that the burning cross was an expressed “viewpoint” within the “free marketplace of ideas”. — See: Butler, Judith. “Burning Acts: Injurious Speech,” The University of Chicago Law School , 1996. pp. 206 - 218 ↩

-

In the case of ACLU vs. Clearview AI, the ACLU sued Clearview AI under Illinois’ State Law for violating the Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA). On Page 16, Section IV A. of the defendant’s motion to dismiss the case, Clearview AI stated the following: — “Clearview’s creation and use of its app constitutes protected speech under the First Amendment. First, Clearview’s collection and use of publicly-available photographs are protected under the First Amendment. The ‘creation and dissemination of information are speech within the meaning of the First Amendment.’” — Additionally, their case argues that Clearview is not subject to personal jurisdiction in Illinois, as their company operates with headquarters in New York and has no servers hosting their data in the state of Illinois. Clearview’s following statements then accuse BIPA of unconstitutionally overbroad, and violates the First Amendment themselves, arguing, “BIPA’s restrictions on the collection of ‘biometric information’ in publicly available photographs violate the FIrst Amendment because they inhibit Clearview’s ability to use this public information in Clearview’s search engine.” — See: ACLU vs. CLearview AI: https://www.aclu.org/defendants-memorandum-support-its-motion-dismiss ↩

-

Fact-check As stated in the LinkNYC privacy policy, “technical information is stored for up to 60 days” and “Anonymized MAC addresses will be stored for up to a year from your last session.” — Regarding cameras, the policy states, “footage captured from any active cameras is stored for no longer than seven days unless the footage is necessary to investigate an incident.” and further that “All data and footage from LinkNYC cameras is subject to CityBridge’s privacy policy.” — CityBridge’s privacy policy states the following: “We will make reasonable efforts to retain Personally Identifiable Information that you provide to us during registration no longer than 12 months after your last login. Unfortunately, the transmission of information via the internet is not completely secure. Although we will do our best to protect your information, we cannot guarantee against access to your Personally Identifiable Information by unauthorized third parties. The security of your data transmitted to or through our Services is at your own risk.” — See: LinkNYC Privacy Policy, CityBridge Privacy Policy ↩